Bernet

Manuel Auad

Auad Publishing

240 pages, $24.95

ISBN: 0966938127

Will Eisner introduces this thorough monograph on Jordi Bernet with the observation: "Here was a man who was producing pure story-telling art." The only problem for English-speaking readers has always been that Bernet's work was rarely translated. As with comics of Attilo Micheluzzi, Sergio Toppi or Alberto Breccia, English speakers are always left wondering what the words mean that are coming out of the mouths of these deft drawings.

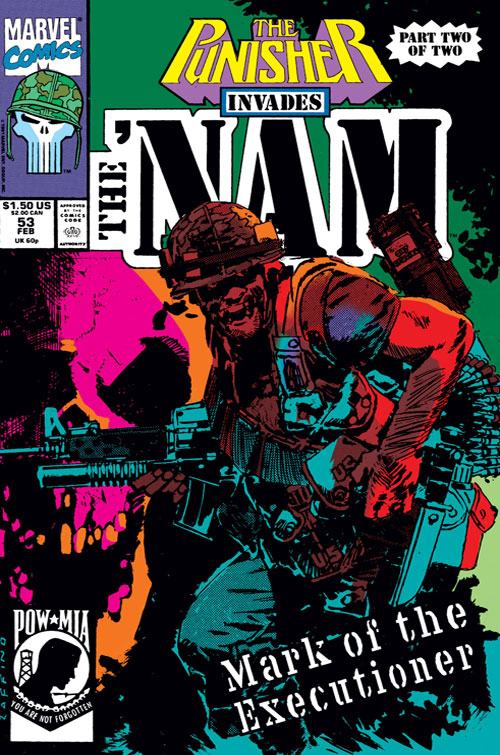

When Bernet's work was previously translated into English it was marketed as simple genre fiction or porn. The publishers never appeared to care about the masterful storytelling that Will Eisner recognized at first sight, and is underneath these classically-styled drawings. Bernet has never gotten the American reception that Moebius, Hugo Pratt, Jacques Tardi or Jose Muñoz received though he has come closer than many.

Auad's publishing of Bernet allows us to now see a fully-rounded picture of this artist. The over-230-page book offers all the different sides of Jordi Bernet the comic book artist, or at least far more than I'd ever seen in English. This well-designed hardcover book begins with two introductions, one by Eisner and the other by Joe Kubert. Both classic American comic artists refer to themselves as fans of Bernet's work. Following the introductions is an insightful, yet brief biography. I only mention that it is brief because, while it does cover all of Bernet's career, by the end I'm hoping for a full-length interview with the guy. The only one I've been able to find in English comes from the pages of Glamor, an Italian pin-up magazine about comics. At the end of Bernet is the first complete bibliography of the artist's career available in English. The biography and bibliography together bring to light a gold mine of little-known information about the artist. I don't get the feeling that, even in Europe where he is a well-known comic artist, there have been too many collections of this kind.

The importance of this influential cartoonist is undeniable, even here an ocean away from him in the United States. That point is driven home throughout the book in a series of appreciations by Bernet's peers and fans, like Sergio Aragonés, Carlos Trillo, Juan Gimenez, Eduardo Risso and Luca Biagini, all of who offer their own insight into the artist.

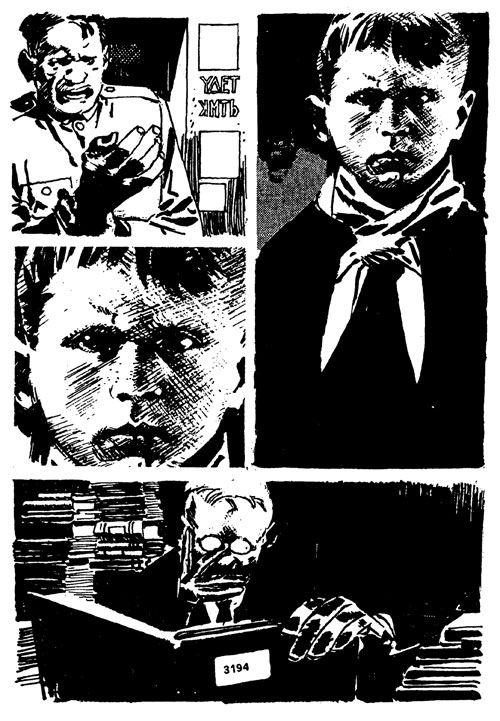

Bernet was born to the Spanish cartoonist Jorge Bernet. He was pushed to reach an early level of facility with his craft when his father died at the age of 38, leaving him the breadwinner of the family. Bernet convinced the editors that only he could serve as artist for the regular strip his father drew, Dona Urraca. The 15-year-old Jordi, who had already began his cartooning career two years earlier, continued his father's humor strip for two years, from 1961 to 1962. Auad's book makes it clear, by examples of early work and in bits of an interview with Bernet, that the artist had always wanted to do adventure strips in the style of his idols, Harold Foster, Alex Raymond and Milton Caniff.

The roots of Bernet's artwork are deep in the history of comics, especially North American ones. The first section of the book is laid out to illustrate the inspirations that drive Bernet artistically. His early work shows the mark of Foster, Raymond and Caniff but then you can see comic-book artists popping up in his style. Frank Robbins (creator of Johnny Hazard) and Bernet were good friends, as indicated in the biography by a great photo of the two with Mrs. Robbins from 1970. Auad's book gives us a sample of an early strip Dan Lancombe from 1968, which really shows the Robbins influence. Another strip (Paul Foran) shows the mark of both Stan Drake and Joe Kubert. While Kubert would be Bernet's most apparent influence,showing up over and over again in his work, it is Alex Toth who seems to hold one of the dearest places in Bernet's heart, as is clear from a great Western story called "Duel at the KO. Coral," written by Enrique Sánchez Abuli in 1998. It is a hilarious account of bear wrestling in the Old West and it is one long tribute to Toth. Throughout the story you see reworkings of an old Toth Roy Rogers story from the 1950s, and the bear's trainer looks straight out of a Toth comic. It's all done with an obvious affection, and you never really get the sense that Bernet is cheating. since it becomes clear during the course of Bernet that this artist loves to draw.

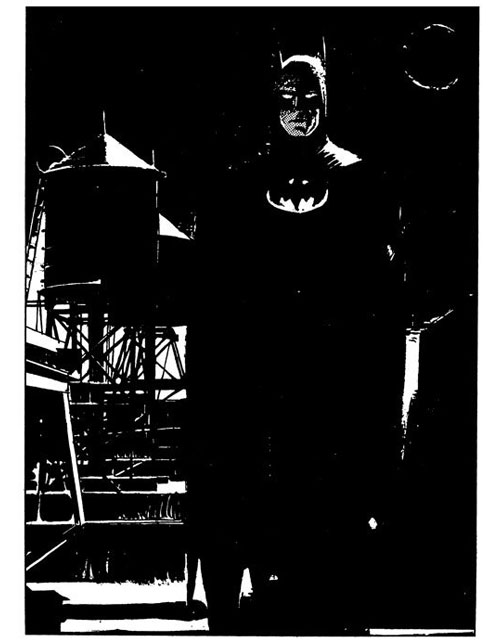

Bernet is often referred to as the most American of Europe's comic artists even by some of the people writing about him in this book. With each of these stories, and the previously published U.S. work, I'm struck by how European his art is. There is a quality in his work similar to the best of Sergio Leone's westerns. In almost all of Bernet's work the approach to sex and violence never looks as rooted in Puritanism as an American would portray it - a complex, adult version of genre fiction that rarely makes it into print in the U.S. but shares a lot with its American pulp forefathers. Strangely though, it never quite feels like the stories set in America are taking place in America. Or maybe it's an immigrant's America. Admittedly, it is more than all that. Bernet makes his characters feel and read like real characters and not just vehicles for ideas.

The best example of this is Bernet's most well known work in the U.S., Torpedo 1936, written by Enrique Sánchez Abuli, previously published in seven graphic albums in English. Auad's book delves well into the history of the series (which ran from 1982 to 2001) with an introduction to the section by Josep Toutain, the original series editor and publisher. Toutain retells the process by which Bernet ended up drawing the series he would become most associated with, and this book also explains in full the beginning of the series as drawn by Alex Toth, who was the one to name it.

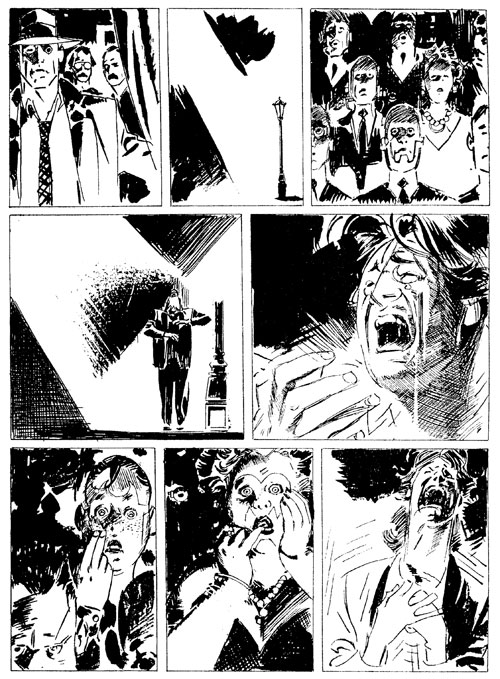

The main character of Torpedo 1936 is an Italian American hit-man (Torpedo) named Luca Torelli. When originally drawn by Alex Toth in two stories in 1982. Torelli comes off as a gangster as played by George Raft. After Bernet takes over the art. Torelli becomes a real-life criminal associate of George Raft's: a ruthless killer with a lot of flair, who is also capable of small moments of conscience. Bernet is also interviewed a bit about Torpedo earlier in the book. "From early on I decided to 'lighten up' the characters. They were so mean-spirited, contemptible, almost evil, that I couldn't draw them very realistically. I decided to have elements of caricatures and thus making them look ridiculous." The Torpedo section of the book also includes a number of great pinup drawings, as well as some beautiful sketches and production drawings that really let the reader in on the process Bernet goes through drawing the character.

Interestingly, the Torpedo 1936 section of Bernet is followed by a collection of ads done in Spain for a whiskey company named Long John. But for this book, these ads would never have made it across the ocean into the hands of American comic art aficionados. The ads are drawn in the same style as the Torpedo series and this is intentional on the part of the advertiser. To an American, these ads really clue you into the different world for which Jordi Bernet draws his comics. It is hard to imagine a cartoonist ending up working for a major advertising company in the United States and being allowed and encouraged - and maybe even selected - for his ability to draw his own personal subject matter. Especially when his main character (a Torpedo) commits heinous crimes in story after story. Manuel Auad does explain that there was a negative connotation to the Luca Torelli character and that Bernet softened and toned down his artwork somewhat for the campaign.

For me, the most interesting series of stories drawn by Bernet is Clara de Noche, begun in 1992 and still being done. These stories represent a more complex side of Bernet and the writing team of Carlos Trillo and Eduardo Maicas (a well-known Argentine radio personality). The stories were marketed as a Bettie-Page style "adult" book when previously released in the U.S. under the title Betty By the Hour. The problem is that there isn't really anything pornographic about Clara, except for the way she is drawn. The stories are a mixture of light comedy with tragedy as told by men (Trillo, Maicas and Bernet) and from a uniquely Southern European point of view. The subject matter is adult but it becomes clear, as with the four two-page stories in Bernet, that there is more to these stories than the pinup-model-looking qualities of its star. Auad's introduction to the Clara section of the book begins "The highly-appreciated Clara de Noche has a job which has to be defined without beating around the bush: she is a hooker." Auad continues to point out the contradiction in making a comedy based on such a profession, "... an uninhibited series, imbued with humor which is redeeming although it is sometimes cynical, yet always playing it fair with the reader, with no corny double meanings." This section of Bernet serves notice that the U.S. market is in need of a complete and well-published collection of Clara de Noche.

Bernet had previously teamed up with the popular Argentine comics writer Carlos Trillo, to create a semi-science-fiction story called Custer in the mid-1980s. As Auad points out in the biography, Custer is an early predecessor to the reality-show genre, albeit a more salacious version. Custer is the main character, a sexy lady whose life the reader follows as if it were filmed by all-seeing TV cameras. Though it is light fare, Bernet brings a touch of his unique caricature to the work. In the story, Custer is followed by a funny little man hired by the network to keep an eye on the star. The character is genuinely funny and lovable in spite of the crass world around him, though even that may be a trick of the camera.

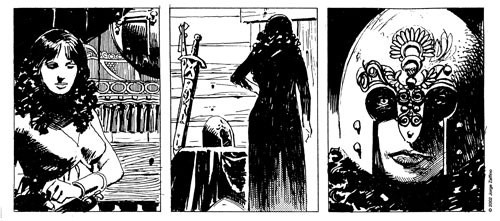

The last 50 or so pages in Bernet are perplexing for me as a reader. They include sections on two older series drawn by Bernet: Sarvan and Kraken as well as pinup good girl art by the artist. Sarvan, done from 1982 to 1984, is a beautifully drawn Frank Thorne style strip, full of wizards, dragons and sexy women - all done, as Auad notes, with more than a tip of the hat to Barberella. Most of my problems with the story only come from a personal distaste for this subject matter, but at the same time I realize that there is a complex artist at work drawing these stories. He does it quite well, but in the end it seems like he is capable of more.

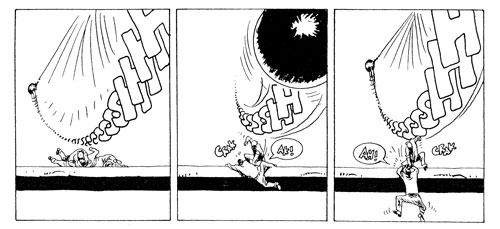

Kraken (1983-86) is, as Auad puts it, ''A long-lived series, [which] tells about the adventures of Lt. Dante, who is at the head of a special paramilitary group in charge of watching over the 13,000 kilometer-long Metropol sewer system." Auad continues to point out that Kraken is "...a pretext for a kind of social and sociological comedy." Kraken is a great follow-up to Sarvan and Custer, in that it demonstrates the full range of Bernet's ability to tell a story. The art, as always, is polished and effective, but more than anything the panels glide along, leading you through a weird sewer world where a monster, the Kraken, is always ready to pounce on the main characters. There is a sense of fear and action, tempered with a psychological subtext of strange machismo that Bernet manages to capture more effectively than almost anyone in comics, something like Richard Corben's most recent work. It is a self-aware genre story that only comes off in the hands of a skilled craftsman. In the hands of most, it would descend into simple minded escapIsm.

Escapism is what most pinup artists depend on: the fantasy of the "perfect woman." Bernet has done his share of pinup art for magazines like the Spanish version of Penthouse. He likes to draw pretty women and he is good at it. There is an escapist quality to the pinup drawings collected in the last section of the book, entitled "Bernet's Beauties." The truth, though, is that the escapism is more innocent and childlike than the drawings done for Penthouse, which are presented earlier in the book. You get the impression that this is a guy who surrounds himself with images of the past and bygone days, and that this extends into his view of pretty women. There is even a photo earlier in the book's biography that illustrates the point. The artist described in this book draws a fine line between porn and eroticism. In the interview from Glamor magazine, Bernet says, "Pornography needs eroticism, otherwise it's junk. Something like that happens, in another field, with violence. If treated with ability, it may thrill you and be exciting. Without that element, it is boring and disgusting." The characters are more like "broads" and "dames" from the old movies Bernet loves, rather than dirty little drawings. This lightheartedness is represented by a little touch of the book's English language hand letterer Hobbie MacGuire. The "I" in "Bernet's Beautie's" has a little heart at the top of it.

Throughout Bernet, we readers are treated to short stories, in the classic O. Henry style. Not just in the sections on Torpedo 1936 or Clara de Noche, but in between them. One-off stories that give you a laugh or creep you out. In each, Bernet is able to make you want to just find out what is going to happen, the mark of a real storyteller. In addition, he is able to draw almost anything, not just pretty women or grotesque men. His illustrations for "Number One Joe," a simple war story written by Abuli, put the reader squarely on the wing of a fighter plane coming back from a mission. We are never allowed to see the pilot or navigator - instead, Bernet uses the plane itself as if it were alive.

The thoroughness of the book is illustrated by an amazing collection of varied work. From beginning to end we are treated with pages of artwork unseen in the United States. From Bernet's early humor attempts in the 1950s, to Frank-Robbins-style adventure strips in the 1960s and much more, the book provides you with just enough, not too much or too little. It makes me want to go out and hunt down the untranslated, 224-page graphic novel of Tex that Bernet did in 1996, as mentioned in the biography, and demand that a U.S. publisher put it out here. Bernet the book also effectively gives the impression of an artist who is constantly working and changing.

All of the work collected in this book is written by others. I wish that Bernet could be coaxed into doing more of his own writing, not that Enrique Sánchez Abuli, Carlos Trillo or others don't fill the job adequately - they do much more so than their mainstream U.S. counterparts. It is simply that Bernet's knack for straightforward storytelling makes me think of the straightforward stories he might tell.

Recent news has it that Bernet is working on books for the U.S. market, that may be published by DC comics as well as a collection of Clara de Noche and more. The Bernet collection comes at the perfect time to introduce us to the full scope of his history in Europe and offer other American publishers a glimpse of what they could be publishing by one of a number of European greats.

[Originally published in The Comics Journal 262, Aug/Sept. 2004.]