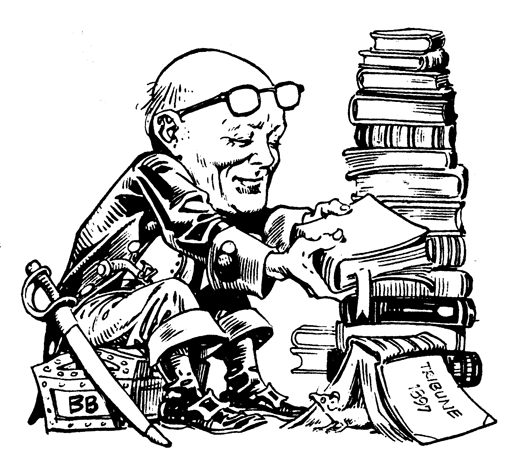

An interview with Bill Blackbeard at the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art on Sunday, April 1, by Dylan Williams. Blackbeard is, perhaps, one of the greatest living resources for comics and the man behind the Smithsonian Book of Newspaper comics. His new book "The Comic Strip Century," a history of the first 100 years of the comic strip, will be out later this year.

Dylan Williams: Okay, the first question is: what projects have you been involved with? That's a big question but it's the thing I'm most interested in.

Bill Blackbeard: Well now, are you talking about the present or…

D: ... over the years.

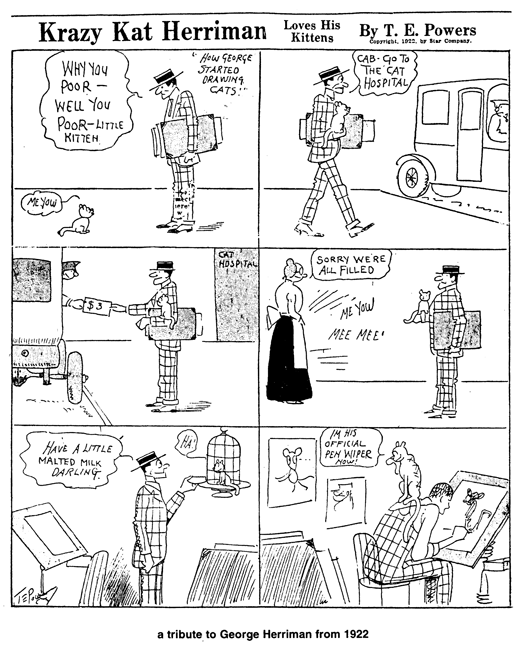

B: If you call projects books, well over 200. Because if you go on a strict count basis you would have to count every volume in the complete Terry and the Pirates or every volume in the complete Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy, complete Tarzan, complete Krazy Kat. These are all series of books that the Academy provided material for which I've done introductions for and provided data and research for. Then there's any number of individual books like Secret Agent X-9, the Kin-der Kids, the current Little Nemo; there was another series of comic book publications like Polly and Her Pals, the Shadow, Buck Rogers...

D: The ones by Malibu.

B: It gets to be quite sizable and of course in terms of major, or what you might call substantial, individual series of work as opposed to series of reprints, I've done the Smithsonian collection of newspaper comics, Sherlock Holmes in America, and I am currently working on a book that will be about twice the size of the Smithsonian book, called the Comic Strip Century. That's going to be two volumes, boxed, about 450 pages, color throughout. It will be another selection of major comic strips from the 1890s to the present. Then I'm also doing the Complete Yellow Kid. Both of these last projects will be out in 1995. The Comic Strip Century in mid-1995 and the Complete Yellow Kid in October of 1995.

D: They're both from Kitchen Sink?

B: The Comic Strip Century is being published separately but it's being distributed by Kitchen Sink.

D: Who's publishing it?

B: David Li, a New Jersey publisher, originally known as Remco. His house title was used for the Little Nemo, Polly and Her Pals, and Krazy Kat color reprint books of a few years ago. Remco was a name cobbled together from the initials of Richard E. Marschall, the editor involved. A lot of money somehow vanished along the way, and David Li severed all professional connections with Marschall as a result, turning to me for the continuation of the Nemo series and the other titles. Li's distributor, Kitchen Sink, will go on getting the books into stores.

D: Wow. That's great news; I had heard they were discontinued.

B: Well, the Pollys were a real problem because they didn't sell well - lacked the titular mystique of Krazy and Nemo, apparently - but the other two will definitely go on. Kitchen Sink is also continuing the black-and-white Krazy Kat Sunday page reprint series, which were dropped when Eclipse folded.

D: Are they going to reprint the Eclipse ones?

B: There are no plans for that at present, unfortunately.

D: Some of those are really hard to find.

B: A lot of them were sold in bulk to remainder shops on the East Coast.

D: Yeah, that's how I got some of them. The color ones were in remainder shops too.

B: The Remco editor also made off with the bulk of the color books and remaindered them in New York under his own authority, without any of the money going to the publisher.

D: Is there one book you're particularly proud of?

B: I like them all. Well, of course I prefer certain strips to others. As far as the books, I try to do the best I can with each. After all, each comic strip character has its own particular enthusiasts. They want to get the best treatment of it that they can.

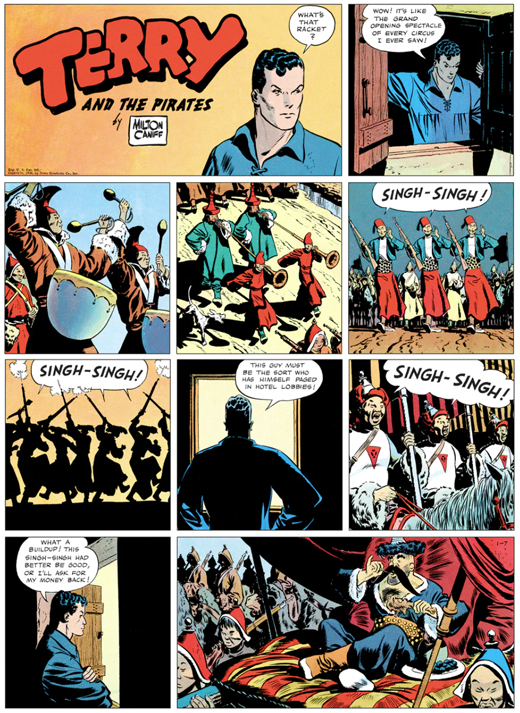

D: The color in the Terry and the Pirates Sunday books are great.

B: There's another story behind that. Originally NBM was more or less content with the earlier black and white Terry and the Pirates series, which contained both the Sundays and dailies. When Remco came out with its Terry and the Pirates book which had color Sundays, Terry Nantier at NBM felt that he could go them one better… do better color work and so forth. He started his series, and luckily, for the collector, when the Remco series went under his continued. So now at least it's all in print.

D: Those colors are just gorgeous.

B: Yeah, they really are.

D: So, when and where were you born?

B: To make an unimportant story very short ... in Indiana, in a town called Lawrence.

D: My relatives are from Bloomington.

B: Really? Well Lawrence is right outside of Indianapolis. It used to be a small town, now it's just become a designated suburb, been absorbed into greater Indianapolis. I was born there in April 28, 1926.

D: Did you grow up there?

B: Not for very long. Came out to California when I was about seven, I think. Newport Beach California.

D: How did you first get into comics?

B: Like anybody else, I read them in the Sunday and daily papers.

D: Which ones were you reading?

B: That's an interesting question because, typically, it didn't take a kid who liked comics very long to find out that the best ones were in the Hearst newspapers. Respectable middle-class parents in those days didn't buy the Hearst newspapers, they bought the other papers, whichever they were, was in whatever town. Of course these papers did not have Mickey Mouse, Popeye, Krazy Kat, Barney Google, Bringing Up Father… all of the strips that kids particularly wanted to read. Not that there weren't plenty of good strips from other syndicates, but King Features had a monopoly on the big names. Like other kids, I had to visit neighbors that did subscribe to Hearst papers get those comics. You could never get unbroken runs, of course. You couldn't get them all together until much, much later.

D: Would you ever clip the stories out and put them all together?

B: There was no point. I would with some of the strips that were in the papers that my parents subscribed to, which in California was the Los Angeles Times.

D: What was the Hearst paper in your area?

B: The Los Angeles Examiner, but Hearst had two papers in Los Angeles… the Morning Examiner and the Evening Herald Express.

D: What kind of schooling did you have?

B: Newport Beach High School. GI bill. Went to Fullerton College. That's about it.

D: Did you graduate?

B: No.

D: What was your intended major?

B: Well... that's the whole point; I hate to get into this because it sounds smug, but it didn't take me long to discover that I knew more on any subject that interested me than the teachers did. So, I was bored out of my skull, and wasn't going to waste any time on things like math or scientific theory. What I wanted to do was pursue particular lines of interest in literature and history and nothing else. Of course, you can't do that in the American school system. You can in the English and Continental systems to some extent. I just lost all interest in school and left as soon as I had used up my GI bill. The bill was nice though, because I was able to put in time at Fullerton and more or less pursue my own interests. I didn't care what kind of grades I got, I was chiefly interested in being funded to spend my time reading and researching, which is what I did during that period. As soon as the bill gave out, I just dropped out of that and went into freelance writing.

D: You wrote for the pulps?

B: Yeah, I had a story in Weird Tales among other things.

D: Which issue of Weird Tales?

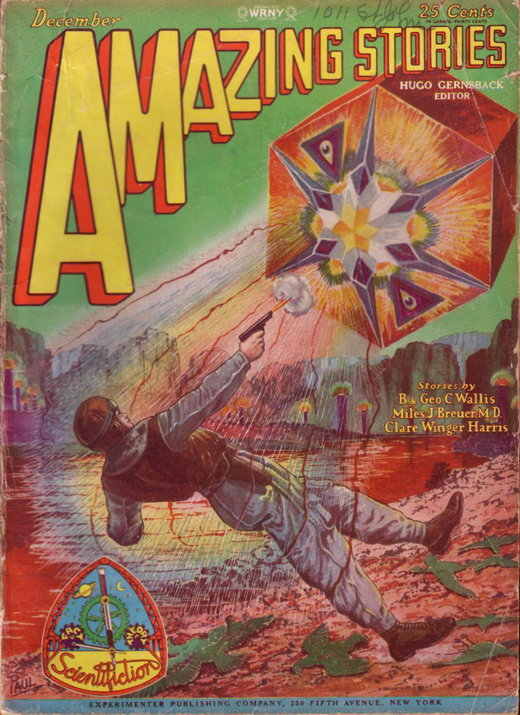

B: It was a story called Hammer of Cain. Weird Tales is still published. There is an outfit that brings out about four issues a year, focusing on the current crop of horror and weird writers and doing a pretty good job. Amazing Stories is still being published. That was the first science fiction magazine, first published in 1926.

D: The covers aren't nearly as good as they used to be.

B: Oh no.

D: I forget the artist's name who did all those gorgeous covers?

B: Frank R. Paul? A guy with two first names.

D: What kind of things were you researching in college?

B: I was completely fascinated with the whole structure of English and American literature and the historical background of this. So, what I wanted to do was read straight through Dickens, Thackeray, Kipling, Poe... all of the major writers. School didn't give me time for that, so I just said to heck with school. It was pointless. What I was doing from the time I was fourteen is what the whole humanities educational structure was supposed to prepare the students to do when they grow up. There was no point in going on; I was already an accomplished scholar; schooling was irrelevant.

D: I felt the same way in regards to art. School is good in that it gives you access to a lot of different things, but if you're already motivated enough to look at the stuff on your own then you don't really need the classroom structuring. There are people who do need it, of course.

B: That's the point of schooling and it always has been here. The reason it was willingly publicly funded here until recent years, was to prepare so many competent individuals for the work force. In other words, that you have people well enough educated to go to work in offices, run their businesses, to take care of the books, make change and that sort of thing. It had very little to do with the nominal cultural goals of creating a well-educated, well-rounded individual.

D: How did you go about getting into Weird Tales? Did you just submit to them?

B: I had a friend who was already writing for Weird Tales. His name was Jim Causey and he wrote a number of Gold Medal novels. He said that they were very friendly at that time to new writers, since so many of the regular writers were in the armed forces or otherwise involved with the war effort. Several established writers at that time went to work for the armament industries because they were paying so incredibly well, the pay was better than writing. They just weren't turning out the same amount of material.

D: Were you in World War Two?

B: Oh yes, I was in the 89th cavalry reconnaissance squad in the 9th army, and I was in France, Belgium and Germany during 1945 when the war was wrapping up. Then with the occupation troops there for a while, and then back to the states.

D: How long were you in the military?

B: The usual duration, what they used to call "duration plus six." As soon as the war was over I was mustered out within a year.

D: With all those writers, did you know any of the paperback writers?

B: Well, actually yes, but that's only because I was a science fiction fan for many years, and quite active in fandom, publishing fanzines and so forth. In that area the writers were so close to the fans that you quickly got to know large numbers of them, from Fritz Leiber to Philip K. Dick and John D. MacDonald. I knew all those guys.

D: Did you know David Goodis, or any of those Gold Medal guys.

B: No, I didn't know David Goodis. He was East Coast pretty much. Jim Thompson, he was in Hollywood, and I was out of that loop. Outside of the science fiction. and to a certain extent the formal crime fiction field, the writers did not associate that much in a group or a genre.

D: What about Alfred Bester?

B: Everyone called him Alf but I didn't really know him.

D: How did you get into collecting? Have you always done it?

B: Collecting, in a sense, goes with reading and research. After a while you discover that libraries either don't have what you want, or have the wrong edition, or you have to return the books. It's pointless. So you quickly accumulate your own library. As a matter of fact, I think that so many American writers and scholars and even ordinary readers have done this, that it's one of the reasons that there is so little support for the public library system. People that have children of course support it heavily, because it enables the kids to find sources for their school work. The general public buys paperback books and usually throws them away or keeps them… I don't think they bother much with the old library system.

D: What do you think of that? Is it a bad thing?

B: I have no opinion at all, I just think that that's the way it is. It's always seemed to me that if you go from one city to another in the United States, you'll find almost exactly the same books in every library, the same writers. In other words, if you have any interest you quickly read through the basic writers and want to find the people that you haven't read that are interesting and the libraries usually don't have these. A lot of people don't realize that the libraries regularly go through their non-fiction and fiction books and just simply throw out any books that have not been circulated in a number of years. At one time the libraries had every major science fiction, mystery, western, sea story, popular fiction writer and every literary writer on their shelves, but as the years went by they dumped them regularly, so they just got down to the handful that were designated as classics by self-established literary critics. They've got all of Kipling but nothing by Captain Marryat.

D: Yeah, I've never read anything by him.

B: Well, there you are. They have all the Dickens and nothing by G.W.M. Reynolds, and so it goes.

D: That controls what people think of as classics and read as classics...

B: And what they think is important.

D: You think that those writers are as important?

B: I think that the quality is there, but I think that they should be surrounded by the other writers from which they emerged, the same writing field from which they came, otherwise their status, their contents, their quality, can hardly be judged in terms of what it meant at the time it was written. A good example is that many of these writers make reference in their text to concepts, ideas, quotations from other books that have vanished from the library shelves and the reader doesn't know what they are talking about and what their reference is.

D: When you started collecting stuff would you lend your things out to your friends? Would you say "Here's a book you have to read." Like you were a library?

B: Sort of. It would depend on how close the friends lived. As a high school kid, in my teens, most of the kids I knew were in the neighborhood so there was no risk in loaning anything, we saw each other at school or around the community. In the science fiction field, which was very close knit in Los Angeles, loaning was not any problem. Subsequently, of course, no, not so much because books don't come back. Since I've established a research center I will occasionally let obviously responsible scholars take things out.

D: When did this (sweeping my arm around to indicate the room in which we are sitting - where I am surrounded by everything from an original Krazy Kat strip, to a complete library of Gold Medal paperbacks, to an immense collection of comic related toys, and of course stacks of original strips clipped from their papers and stacked in order... about 1/8 of the Academy) collection start?

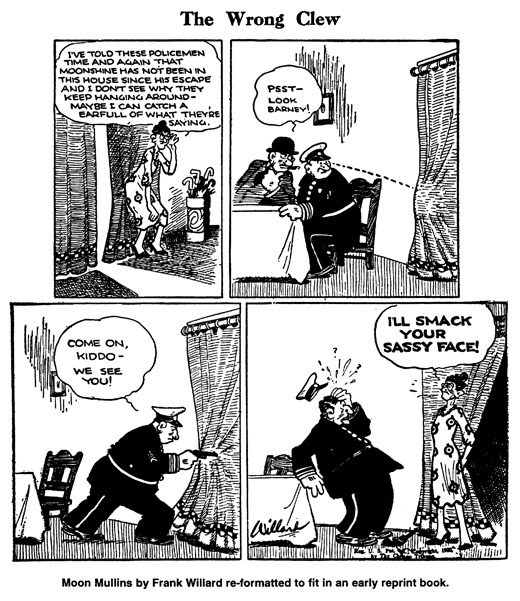

B: Well, that's an interesting story. It all came out of the obvious need for a good sound history of the comic strip. I wanted to write that in the late 1960's, and I quickly discovered that there was no research center for comics of any kind. There were no runs of American comic strips at the Library of Congress, at the New York Public Library, at the Smithsonian, at universities. Nothing at all in terms of individual structured sets of material... like all the Moon Mullins, all the Dick Tracy, all the Mickey Mouse, all the Popeye. These things were there, but only in the sense that they were bound into the files of newspapers which the libraries then had. The problem with that is that there never was any index to the comic strips in newspapers. No one ever prepared such an index. Many papers would arbitrarily drop comics from one time to another. You might start reading a particular strip in a particular newspaper in a particular city, and you would discover that the paper dropped the comic strip and it wasn't repeated in any other paper in that city, so that you would have to go to another city to find another bound file to continue reading that particular strip, meanwhile having to give up reading all the other strips that were running in the original paper. You can see what kind of hopeless complications you got into here. The syndicates kept none of their old comics. Every ten years they would clear out their temporary storage space and just send it off to the city dump.

D: The originals too?

B: Original comic strips were in many cases considered worthless until the 1950's. You hear horror stories of people who would drop in on King features, and for one reason or another the editors would take them back to the room where they had various documents and records stored, and there'd also be great stacks of original comics. These would fall off the shelves, fall on the floor and clerks and people would walk on them as they went through, kicking them out of the way... Alex Raymond strips along with Harold Fosters and all sorts of things.

D: Why do you think the artists weren't interested in keeping this stuff?

B: Because it was just like manuscripts for fiction magazines. The original comic strips were units by means of which the artists transferred the work to publication. The publication was the end point of the work. The original was just a piece of paper. It was not regarded by anybody, including the cartoonist, in the 20's, 30's, and 40's, as art.

D: It was in the 50's that it changed?

B: In the late 50's a market began to develop for it. There had always been enthusiastic young cartoonists and readers that would write in to a cartoonist and sometimes the creators would send them back an original, signed. Those were just regarded as trophies or souvenirs. Other cartoonists would put the work up on the wall near their drawing table. They'd just have one of each as example. They might say, "To my good buddy Fontaine Fox," or "To my writing friend Billy DeBeck," ... things like that.

D: You've seen originals like that?

B: Oh yeah, they still turn up. Lots of them were just thrown out when the cartoonist died. His wife would take them off the walls and just throw it away. Original comic art had no known commercial value. Money didn't take part in it, they were given away to people who were enthusiastic or just thrown away. That's why so much of that stuff is lost. In any event, the syndicates didn't keep originals, they didn't keep proofs, they didn't keep working copies, they didn't keep tear sheets, they didn't keep anything because the idea before the 50's was that there was no value in an outdated comic strip. "Who would want it? It'd been printed. It's dead." So, I wanted to do a book on the History of comics and I found that there was no way to research it. I was more or less at my wits end because there was no material at the syndicates. The artists were scattered all over the country, and they also were very careless about their own files. The older cartoonists who had moved would just dump their earlier things. Only a few cartoonists, like Milton Caniff, Chester Gould, Harold Gray, Roy Crane and George Herriman were sufficiently concerned with the work as a body of work, in the same way that a major novelist would be concerned, so that they would keep everything. They saw the worth and the developmental structure, the value of the developing structure of their work as of continuous importance. They not only had need to refer back to their earlier work in developing their current stories, but they also had a sense of the total value of what they had done. Harold Gray kept 90% of his originals and that all went to Boston University. Chester Gould kept most of his original art, proofs and such, and I think that's all in the hands of the Gould family, as are Herriman's. Milton Caniff's stuff all went to the University of Ohio. He kept virtually everything in terms of proofs and in terms of originals. The point is that this was very uncommon. I had nowhere to go to do any research. Then in the late 60's, the American libraries began to get budgeting to buy microfilm replacement for the newspaper files. They had come up with this notion that newsprint was internally self-destructive. That it was decaying at a certain fixed rate every year and before long you would open a newspaper volume and it would all be dust. This, of course, was paranoid fantasy. It had no basis in reality at all. Although the reasoning behind the replacement was specious, the real reason was that the librarians wanted to get rid of all those heavy twenty and thirty pound newspaper volumes that had accumulated over the centuries, just clear them completely out of the building. So, they actually engaged in what was quite frankly bureaucratic fraud. They would be photographed in the newspapers holding a crumbling volume of newsprint. Saying "Here's what's happening. We've got to get rid of it!" So the civic authorities that held the library purse strings were persuaded to untie them and allow the library thirty or forty thousand dollars for complete microfilm runs of newspapers to replace the bound files they had already spent thousands of dollars on in putting away and storage. So the whole thing was for the benefit of library bureaucrats. It had no other purpose. They were relieved of this enormous annoyance, from their point of view. They could fall back on these little boxes of micro film. This way they could also get rid of the people they most disliked in libraries, which were the people that came in and sat in the newspaper room for hours and worked crossword puzzles in old newspapers and fell asleep on the volumes, who just bothered the heck out of them. The whole point is that none of this had anything to do with preserving the past or maintaining physical access to the documented history. A librarian scam is what it was. At any rate, it worked! I learned that libraries were then in the process of dumping this stuff as they got the microfilm in hand, and the San Francisco Public Library was the first one that I heard about on the coast that was going to move all of its newspaper volumes out. They had a large number of volumes from other sources they had stored and they were also going to dump those. Well, I discovered that the library in San Francisco, as is true of many other libraries, was bound by its charter agreement with the city not to give anything away to the public. The library could not give any of its books or papers to any private citizen and they could not sell them, only transfer them to another institution, or destroy them… so I become another institution. I became a non-profit organization: the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art, complete with board of directors and so forth. From then on, I became a We. We, the Academy, was then enabled, to the great joy of the San Francisco Public Library, who didn’t have to spend money to haul this stuff to the dump, to come in with some strong guys with strong backs to move all these volumes out to a sorting center that I set up. I had arranged to remove comics en masse from newspapers, in order to preserve them in sequential order, Sunday comics, daily comics and so forth. Now, because the comics were spread over many newspapers, there wasn't really a set of papers in San Francisco that even began to give access to the full record of comic strip publication. So, when the Library of Congress began to do the same thing, I turned to them. At one time they had six acres of bound newspapers from the entire nation in Alexandria Virginia. They have now despoiled and destroyed every bit of that, totally wiped it out of existence and replaced it with this greasy, scummy, scratchy microfilm, of course, which is the only record they've preserved. No color in microfilm, all the color in the papers was wiped out. The same bureaucratic logic: let's get rid of all this dead weight which only a few scholars use and screw them. I picked up a lot of those papers from the Library of Congress, from the New York Public Library, from the Chicago Public Library and brought those across the country in Ryder rental trucks to my sorting center.

D: What was the date on that?

B: That would have been in late 60s, early 70s, and pretty much through the 1970s; in fact it's still going on to some extent. There are still some libraries that are disposing of material. The state library in California supplied us with an enormous amount of material. One time I had this phone call from the state library and the staff announced that the state had told them that they had to put in a fire safety corridor. The library is in the state's court building in Sacramento and they had to put a fire corridor through the lower level of the courts building, which is where most of the state libraries newspaper files were kept. So they had to get rid of all of their out of state newspaper files at once, "Can you clear out all these tons of newspapers in two or three days?" they asked and I said I could do it. I got up there and picked up papers like the New York World (which was a crucial newspaper), Chicago Tribune, dozens of them.

D: Was the World a Hearst paper?

B: No, it was an opposition paper. That was the paper that Hearst went to New York to compete with. In any event, that had all of the early Yellow Kids. It was one of the last print files in existence of the Yellow Kid. I was doing all that and when I was part way through that, it occurred to me that not only were the comics crucial items to be saved from this holocaust, the newspapers themselves had to be preserved in many cases, because once they were gone, they'd be gone forever. The layouts of the more sensational papers were of extreme graphic and historical interest. The New York Times reads just about as well on microfilm as it does in the bound file, so there's not a lot of point in doing anything there... just a concentration of data, facts and words. The sensational papers, though, had a little artistic fit every day, in terms of splashing sensational headlines.

D: Was there color printing?

B: Oh yeah, a lot of color printing, headlines in green, blue, red, color pictures, especially where there were crimes and disasters. We've kept many of these files at the Academy complete with the comics still bound in. We have a fundamental collection of the Hearst newspapers from the 1890s through the 1950s. This includes the Hearst newspapers from Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle and so forth. Those are all here for cross referencing. We also have a large collection of the old American tabloids, the New York Graphic, the New York Daily News and so on. All of those are here in bound volumes. We are the only source for hard copy newsprint in the United States because the libraries have thrown it all away and the newspapers have, by and large, despoiled themselves of their own files.

D: Are the people who run these libraries are aware of you, so when they get rid of it they know to call you?

B: Yes. Younger librarians are already aghast at what their predecessors did. It's really a generational thing. When the new people come in and they develop an interest in the past and want to look at the old files… they want to know about it, and they find that it's all been destroyed. Then they're horrified. They aren't bored with it like their predecessors were. The funny thing is, that everyone thinks that they know what is going to be worth preserving in the present and they never do.

D: I was reading somewhere that nostalgia is a modern thing. Longing for things from the past didn't start until the 50's.

B: Well, I don't think that's true, but it's true that people weren't always aware of the value of a thing that was around when they were growing up. Plenty of people in the 1930's had nostalgia for the dime novels of the 1890's.

D: Would people collect those?

B: Enormously! They would pay big bucks for things like Buffalo Bill, Nick Carter, the James Boys, Old Sleuth... all of these magazines were going for big bucks, like comic books are today. Really what keeps interest up is the continued publication. The dime novels came to an end as a publication concept around 1910-15. They disappeared from the newsstand, they weren't seen, nobody bought them or read them. So, when the generation that grew up with them and loved them and collected them died out, so did the collecting interest. Of course, there was no later nostalgia for these particular things, you couldn't have it for something you had never seen. The same thing is happening to the pulp magazine. The pulps disappeared in the 1950's and now many people don't even know what a pulp magazine is. There are people that think a pulp is something like the old True Detective magazine because that's all they have ever seen around that looks old. Comic books are still being printed though, so as a result, that collecting balloon hasn't burst. Because of the interest in the current comics in the collecting field there is a concentration of renewed awareness of what you call the golden age and the silver age, so that the value of these collectibles holds up. Now, in the normal course of things, comic books from the 30's, 40's and 50's would have gone through a cycle of high value, then a total collapse, so that by now, normally, you would be able to pick up Famous Funnies or Action Comics for a couple of bucks because nobody would care about it or want it. But, you have got this enormous hype now generated by the dealers, which convinces everybody that if the value goes up then it means a college education for them if the just buy it now and put it away. Eventually that balloon will also burst. I think that comic books, as such, and to a certain extent comic strips in the early decades of the next century will probably be replaced by computer printouts of some sort, so the whole concept will go... we'll see.

D: Going to a book fair recently, I saw all these collectable books, like a Ulysses first printing going for $50,000. It makes me crazy knowing that no one's ever going to read it, or even look at the words on the page. It stops becoming a book. It's just a commodity.

B: It's an investment. Look at the comic books that are wrapped in plastic bags and put away in bank vaults. What's the point of having an Action #1 if your banker has it?

D: I don't understand that mentality!

B: Well, it's idiotic because the entire thing has been reprinted several times over, including those large reprints that DC brought out which are delightful. Who would want anything else?

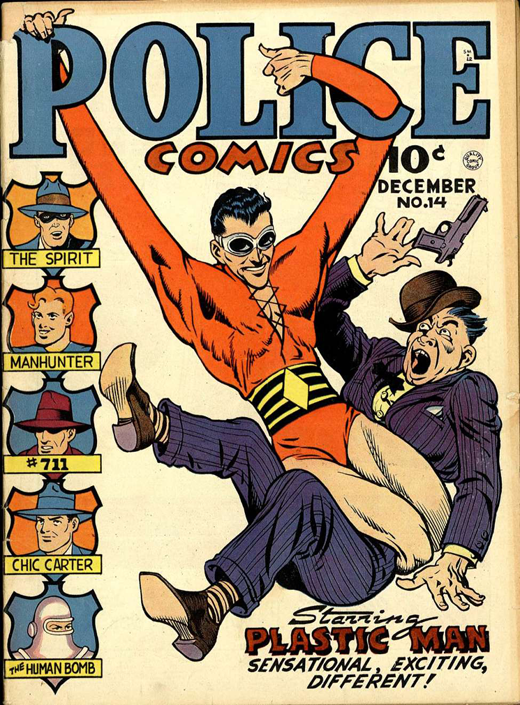

D: There's stuff like Plastic Man that you can't find anywhere else than in the original comic, and those investors drive the prices out of a reader's range.

B: The only reason for collecting or picking up anything that was printed in the past is because there is no contemporary equivalent available. If you're going to read, as you say, Plastic Man, then you're going to have to go back and buy the old comic books. Some of it's been reprinted but not a great deal.

D: DC was planning to do one but...

B: They have done any number of books on their Batman and Superman heroes but they haven't done one on Plastic Man yet. They did do one on Captain Marvel though. Occasionally, though, you get out of left field an unbelievably unexpected reprint of a classic comic book, like the English reprint of the Captain Marvel versus Mr. Mind series of stories. It has no reason to exist, because it doesn't have any market. By publishing it in a limited edition they were able to get a certain amount of money out of it.

D: It got remaindered though.

B: That's the problem. It obviously didn't do as well as they had hoped. But at least we have the book. Otherwise, collectors were going crazy trying to get that whole story in the thirty to forty issues of Captain Marvel that that story appeared in, all of which price out at fifty to sixty bucks each in any kind of decent condition.

D: Do you know the publisher who did that?

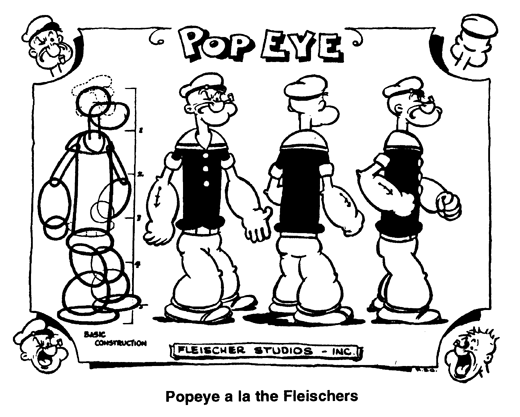

B: Hawk Books of London who published my book on Popeye. [pulls out hardback Popeye book with Popeye framed in a life preserver on the cover]

D: I've seen it but never got to look through it.

B: Well, it had a low distribution here. It was imported, and because of the pound/dollar differential it was expensive.

D: What do you think of the Fleischer cartoons? Not just Popeye but Superman and so on...

B: The animation on Superman is marvelous. I don't think much of the source material, but as animation it's a marvelous piece of work. The animating of humans was very well done, considering the period.

D: I heard they had an enormous budget.

B: Whatever it was, it returned its investment because Superman cartoons were hugely popular.

D: They were played before movies?

B: Sure.

D: Something my generation totally lost is cartoons before movies. We were introduced to all the Warner Bros. cartoons through TV.

B: Occasionally movie theatres will still put in a classic cartoon just to amuse the audience. There's no structure though. You can't expect it.

D: The Castro theatre is pretty good at maintaining all the things that are great about film. I went to their widescreen festival to see the Wild Bunch twice, and was amazed to see that the theatre was packed both times. It kind of restores my faith in people to think that all those people wanted to see this "old" movie.

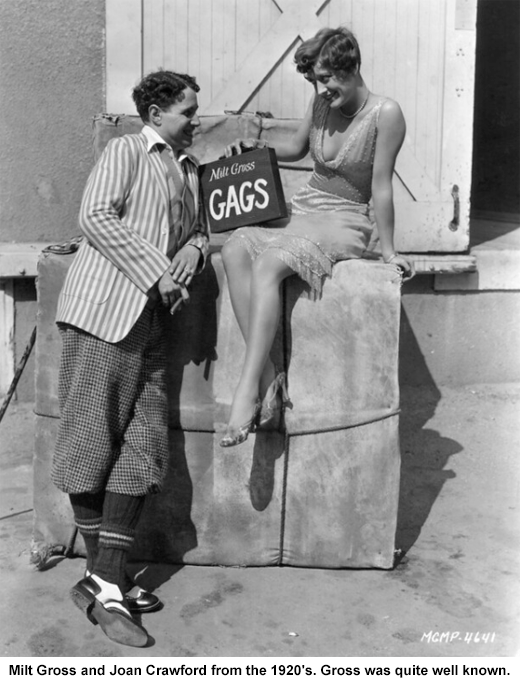

B: What you have got here is this renewal of interest in the past. Most people today are just as aware of Spencer Tracy, Joan Crawford and W.C. Fields as people in the 30's were. These people are publicized, written up and seen on television continually. This is not true of the general television viewing public, the people that watch just the commercial channels or watch these terrible daytime talk shows. These people don't know anything about anything. Obviously, the aficionado of the Castro and the college level kids are extremely interested in finding out about the past of movies and comics and books in general.

D: That's one of the few pluses of working in a comic store. I get to play some part in maintaining a public interest in old comics. Every time I get somebody into Popeye, that increases the chance that Popeyes will still be in print twenty years from now.

B: Happily for the comic strip, the interest in cartoons sustains an awareness of the Popeye character so when the Segar material, the comic strip material is reprinted, there's a ready-made audience for it. They see the Popeye name. Segar supervised the Fleischer animated cartoons, by the way. That's why they are so good.

D: Even the color ones?

B: Right.

D: Did he have any say with the voices being muttered like that?

B: It's hard to say. I can't find anything on that. I think that was a studio development, but it may be that Segar had approval on it. The voices are perfect.

D: It's rare that you find that, although the Supermans were pretty good too.

B: Yeah, you accept that as Clark Kent. The Betty Boop stuff that Fleischer did was great.

D: I just heard that they are doing a new Felix show that Milton Knight is in charge of and they are modeling it on those Betty Boops.

B: Disney has released a Betty Boop short. I don't know if they did it, but they released it, and it's very well done. It's in color and it's twelve minutes long.

D: Wow, where did you see it?

B: On the Disney channel. They show it occasionally.

D: I don't get cable, I should though. The East Bay just got the cartoon network, and I hear it's pretty good. The problem with getting cable and being an artist is that I would be watching it too much (for visual stimulation). There's so much good stuff on, old movies and so on.

B: Well, yeah, but you can control it. Tape it and watch when you have to do some filler sketch, doing a background, or filling in blacks, dull stuff like that.

D: Once you had set up the Academy would local artists, like the underground guys, come out and visit? B: Yeah, all of them. We have a complete file of all the undergrounds. Issues of Zap that were sold out of knapsacks on Haight Street. I was there, I bought them.

D: You saw it as an important movement?

B: I saw it as an important movement in comics. The work was very imaginative, very inventive. There was a lot of great stuff.

D: Did a trip to the Academy have a big influence on those artists?

B: What would happen is one or two visits in depth and then they had to return to their own work because they had a lot of work to do, and of course they were socializing a lot, in their own groups. Everybody was here from Crumb to Moscoso to S. Clay Wilson. He just did an illustrated edition of Hans Christian Anderson.

D: Which is such a weird idea!

B: (Laughs) It was the first time he's ever been disciplined. He couldn't put in all the fucking.

D: What kind of person comes to visit the Academy now?

B: Someone who's interested in any of the material we have here for research. They just call up and make an appointment. Could be somebody researching mystery fiction, science fiction, newspapers, material in newspapers, comic strips, pulp magazines, dime novels, penny dreadfuls.

D: Do people come from Europe?

B: Oh yeah. in fact they know more about us in Europe and on the East Coast. In San Francisco they don't even know we exist. Herb Caen hasn't ever mentioned us. It's gotten so that it amuses me now. He thinks he knows all about San Francisco and he doesn't even know that we're here. The establishment San Franciscans are a very insular lot.

D: Yeah, that's really true. They never go to Berkeley or any other place in the Bay Area. It's a tight knit little community.

B: Unless you're a restaurant goer or frequent the bars, you don't run into these people and they don't know anybody else.

D: Do you correspond with people too?

B: I don't have a lot of time for it, except for business and research. I used to be a demon correspondent back when I was a fan. I wrote loads of letters to people.

D: What are your personal favorite strips?

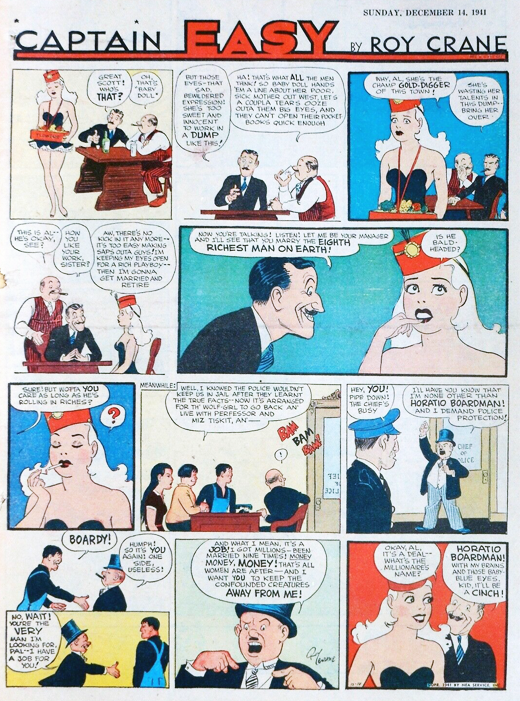

B: Well, to a certain extent they're reflected in the books that I've edited. You can almost look at those... it would be Polly and Her Pals, Popeye, Secret Agent X-9, Terry and the Pirates, Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy.

D: Humor type things?

B: Humor strips and the serial strips that had a strong humorous component, of course that would mean Dick Tracy. On the other hand, the other strips that were grit-toothed and deadly serious, like Flash Gordon and Tarzan, that sort of thing doesn't do that much for me. I admire the art, but the story line is just too esoteric, and of course it wasn't very good.

D: Was Burne Hogarth writing the Tarzans while he was drawing them?

B: Hogarth did most of his own script work. There the artwork is so overwhelmingly good that you find yourself just looking at the art and forgetting all about the story. The story is just a thin tenuous thread that sort of ties the art together, but it's not terribly important to the content. It's not terribly logical either. "How can we justify a big splash panel this week?"

D: Do you think the fact that Krazy Kat and Popeye hold up so well, is that the people who were doing it were conscious of the potential of it?

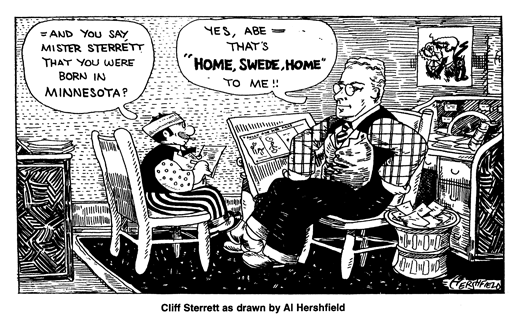

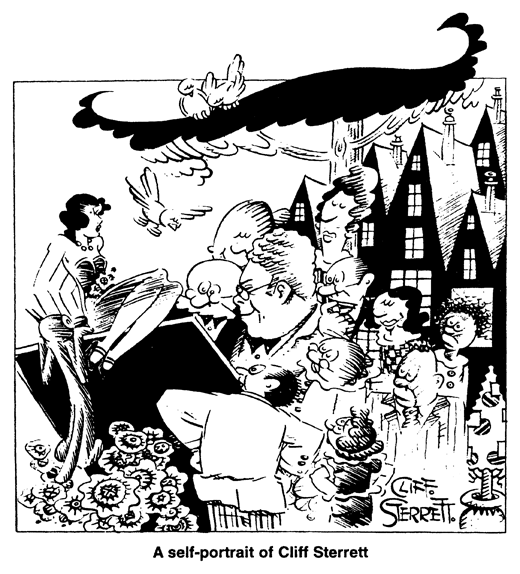

B: I think that's quite true. You'll find that, with some exceptions, the comic strips that were the work of artists that by and large avoided assistants, when they possibly could, because they loved what they were doing so much that they threw themselves into it, were the better strips. There are some exceptions: although Al Capp hardly lifted a finger on Lil' Abner after the 1930's his concern with the storyline and the characters was so strong for so long, that the quality held up, more or less to everyone's amazement. Generally speaking, the strips in which the artist more or less abandoned ship, like Ham Fisher's Joe Palooka, were just totally stupid and dull because he had the name and he had the character, and a certain juvenile interest in boxing held the public's attention. On the other hand, you had people like Harold Gray, Chester Gould, Herriman, Cliff Sterrett. These are people that didn't want any interference, or the least amount of ghosting or outside handling of their work. Now, the more realistic cartoonists such as Caniff and Crane, simply because of the sheer volume of work involved, would have to bring in people to fill in backgrounds, to letter dialogue balloons and things of that sort.

D: Crane always had great assistants like Leslie Turner.

B: Exactly. I don't know if you realized this but there were certain cartoonists that would use a ghost because they were ill or on vacation, but they were so concerned about the attribution of their work that they would not sign anything that was not their work. You'll see, for example, in the middle of Wash Tubbs in the late 30s, there's a sequence of about two months of strips which are not terribly well drawn, this was before Turner, they are just adequate, but Crane didn't sign any of them. He provides the storyline, the dialogue, but..

D: Did he take a break?

B: He was ill, I think. Cliff Sterrett made several trips to Europe, and while he was away people like Doc Winner filled in. When he semi-retired in 1934 he dropped the daily strip, but kept the Sunday, so his signature was only on the Sunday. The daily, of course, had a printed byline because the syndicate insisted on that. The dailies were done by Paul Fung. In Secret Agent X-9 there's a long sequence in which Alex Raymond's work is not there, and neither is his signature.

D: Is that in the book?

B: Yes, that's the complete Secret Agent X-9 as bylined by Dashiell Hammett. Raymond bylined for some time after that. It's not the complete Secret Agent X-9. It went on for some time after that.

D: Was Cliff Sterrett influenced by the art movements of his time?

B: He in particular was. That's one of the reasons why he went Europe, to soak up some of that. Stylistically there were noticeable changes in Polly and Her Pals over the years. The awareness of Academic Art by cartoonists was nothing unusual. Rudolf Dirks, who invented the Katzenjammer Kids had paintings in the famous Armory show right along with the ashcan school.

D: I knew about Feininger, but I didn't know Dirks was in on that too.

B: Yeah, they were together. Dirks had regular exhibits of his paintings for decades.

D: Have you seen the paintings?

B: They are just what you would expect. They are intelligent and well done. Not what we're looking for in this work. It's a different world all together.

D: It's neat to see highbrow cartoonists, though.

B: They weren't very highbrow.

D: Feininger seems to have really broken into that world. Non-comics artist friends of mine actually know of him as a fine artist. I'm amazed that he's that well known as an artist when he's barely known as a comic artist.

B: He's obscure as a comic artist because he only did that one strip for one year. If he'd kept on things might have been different.

D: Do you find that a lot of people grew up reading the Smithsonian book?

B: Everybody, everybody bought the book. It was enormously well promoted by the Smithsonian press and by the Smithsonian Magazine. It's sales by mail, year after year, made it one of the best sellers of that year, but of course, the official New York Times best-seller list is based on bookstore sales, not on mail sales. It's status as a best-seller is known only to the Smithsonian and myself. My royalty checks on that for ten years were very good.

D: It was in print for ten years?

B: Oh yeah, longer actually.

D: How many copies did it sell?

B: I'd have to go back and check, quite a number through each edition.

D: I got it as a present from my Grandparents. They knew I was into comics and they wanted to get me into a little more highbrow stuff so they got that for me.

B: (laughs) They regarded that as highbrow because of the name, Smithsonian.

D: That and they grew up reading those early comics in the papers.

B: There's still people that think that all the comics must be in the major American research centers. They find it hard to believe that there isn't anything except what I have here. Many think, on the strength of the title of the Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics, think that there is a Smithsonian collection of newspaper comics in the Smithsonian, and of course there is nothing.

D: There's nothing? I figured that they'd have microfilm or something.

B: No, they don't care about it.

D: You're kind of an annex to the Smithsonian.

B: In comics, the Smithsonian is an annex to us.

D: Did you have something to do with the comic book book they did?

B: I was supposed to come in on that, and I didn't want to include any of the superhero material. My reason was, it's all in print, it's everywhere. Why on earth waste space when there's all of this great comic book art which has not been reprinted. The editor wanted to sell the book, so he said "No, you've got to have Superman and Batman."

D: It's neat that it had Little Lulu in it, that was the first time that I had read Lulu.

B: It had good stuff in it, but I would have had several other things as well. The people that edited it were quite competent, but at the same time, the book never developed any status or prestige. It had a couple of printings and then disappeared.

D: It was just things you could get elsewhere. Even those EC things... those are/were everywhere thanks to Russ Cochran and the like. What would you have put in it?

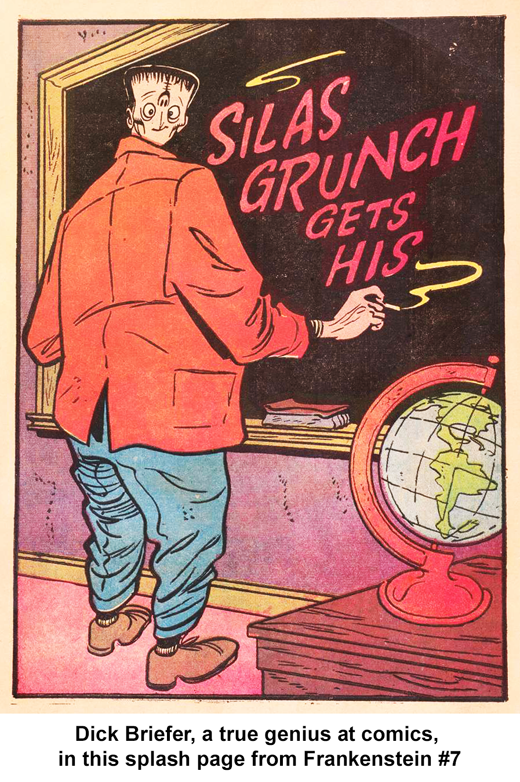

B: More Wolverton, Jack Cole, Dick Briefer, Sheldon Mayer, Boody Rogers and Ed Wheelan. I just couldn't see giving another boost to these meretricious superheroes, which I think are sub-moronic. Not the way that they are being handled now, but the way they came into being in the 30's, 40's and 50's. Now you have a lot of sophistication in the technical handling of the material that gives it a little more panache, different concepts. But, the six or seven year olds that jumped around on their beds reading Superman, in the early years, that was exactly the mental level that the thing was created for. That was its audience. It had no substantial worth except in the incidental touch of Shuster art, which is often nice, and the Bob Kane art on Batman. The content, the storylines, were imbecilic.

D: I have that problem with Lou Fine’s work, the art is great but the story… I just can't get past the first page.

B: Superman stuff in the 40's and 50's descended to a depth that has never been paralleled since.

D: I don't know about that. Have you seen some of Image's comics?

B: No. Pretty bad?

D: Pretty bad!

B: The funny thing now is that young kids buy the comic books, but they don't read them because the stuff that is on their level is on TV. They are buying the comic for an investment. They've got the idea that if they put them away they'll make bucks.

D: Working in a comic store, I'm beginning to see the tide turn. Our bestselling books are Hate and Eightball, Fantagraphics titles. I'm praying that, maybe, people will get out of it.

B: Why do you think the big ones are buying up the publishers. DC and Marvel are protecting their flanks by buying outfits like Malibu and so forth. That's where the future may lie.

D: Is there any particular strip that has been lost to time that you think is particularly important?

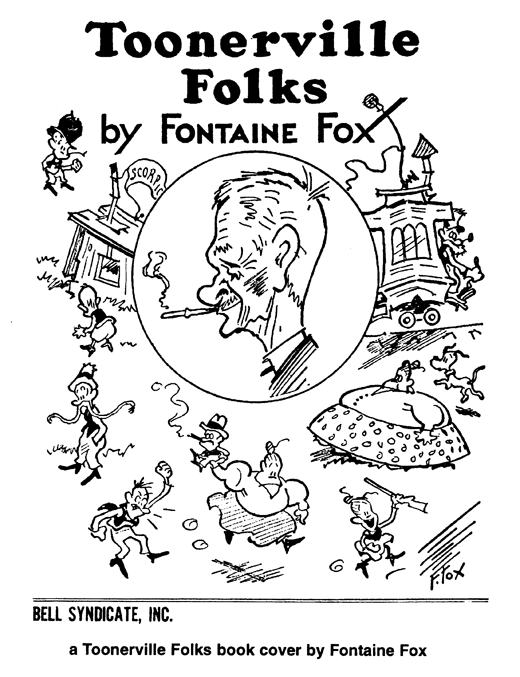

B: Dozens. There's Danny Dingle, Looy Dot Dope, Bunky, Hairbreadth Harry... it's hard to say because I can't always be sure of what people know or they don't know. I'd say Toonerville Folks, but there may be a certain awareness of the Toonerville Folks and the Toonerville Trolley.

D: There was a book that came out in the 70s of that strip but I don't think people know about it.

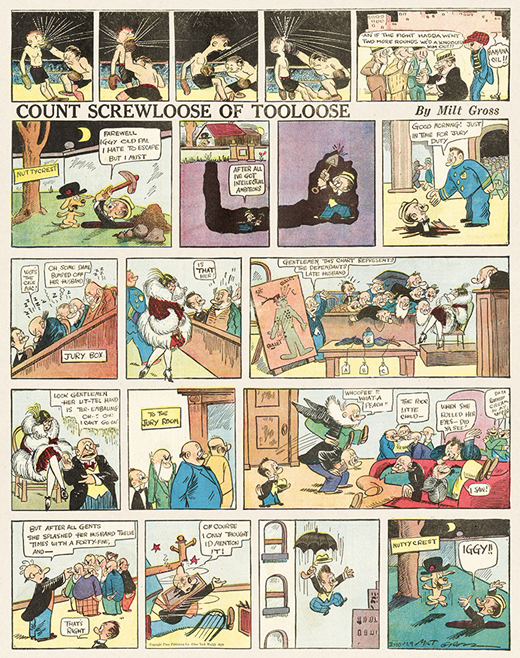

B: I don't think so... there's Everret True, there was a reprint of that but it wasn't very well done. There's the whole Milt Gross line of material, Nize Baby, Count Screwloose of Toulouse, Dave's Delicatessen. Needlenose Noonan, there's an odd one for you, Red Barry but that has had quite a bit of reprinting. It was a major crime strip and almost as good as Dick Tracy. Jim Hardy, I can go on... the Bungle Family which is not too well known now, which is one of the great strips. It's the best thing before Ernie, if you like Ernie.

D: Ernie? What's Ernie?

B: You don't read Ernie in the Sunday comics in the San Francisco Examiner? Ernie is the intrusion of the underground into regular comics.

D: Zippy?

B: Ernie, Zippy is tame compared to Ernie. Zippy is so establishment he squeaks. Ernie is totally anarchistic. I can't believe you haven't read it.

D: I'm the kind of guy who opens the section and only reads his regular strips. I know I shouldn't, but I do.

B: It's the only way you're going to find anything.

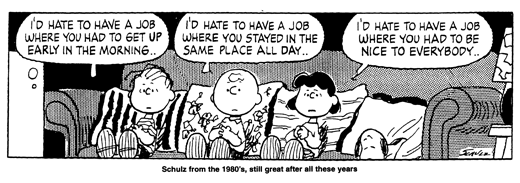

D: I'm so used to thinking that there's not going to be anything good in a modern strip section. I read Schulz and maybe a couple of others.

B: He's one of the one or two other people. Bud Grace is the guy that does Ernie. See, I just made a reference there to try and explain an older strip with a new strip and you don't know what the new strip is. It's possible to say that there are new strips that are not very well known that are excellent.

D: So, you think that there is stuff being done now, of worth?

B: We have a kind of a renaissance in comics in the 90's. Generally, the average level of newspaper comics is higher than it has been since the 40's. In terms of quality and in terms of the limitation of the medium, the small panels and the refusal of the syndicates to handle much of anything that doesn't involve kids and pets or families or working women. In terms of those limitations, what you've got is very good.

D: I kind of miss the serial thing. I grew up in foreign countries reading Mandrake and the Phantom.

B: How could you read Mandrake?

D: They were printed in India.

B: (Laughs) Yeah, but the strip... at your age... it was so bad.

D: I was a kid and he had a costume on.

B: That was one of the most preposterous things about the strip. Mandrake and Lothar walking down a major city street...

D: Wearing a silly-ass costume!

B: ...and nobody would pay attention to them.

D: I just meant the idea of it being serialized. I look at the Phantom and I'm not particularly interested any more.

B: Well, it (laughs) was better than Mandrake.

D: It was just the idea that I could read this ongoing story, where what was going on today had something to do with what was going on three days ago.

B: The concept was there, without the content.

D: Schulz tries to do it these days.

B: The story running for a week is pretty common in newer strips. Running more than a week is less common, but it does happen. It happens in Ernie.

D: It sounds like the greatest strip ever.

B: Generally speaking, the editors and syndicate people are afraid of anything long because they think, and they're probably right, that the readers don't have an attention span that will carry them through for any long period of time. A lot of people don't read comics every day.

D: It seems like a self-fulfilling prophecy. The syndicates (in the 50/60's) were trying to second guess people by saying that nobody had the attention span, and so they made it true.

B: This is true of all media. This self-fulfillment, you see it in motion pictures and in book publication. There used to be a popular idea that the readers wouldn't accept more than one novel from a given writer in a year in, say, mystery fiction. The writers not only wanted more money, but they also had more stories to tell, so they would publish under pen-names. Generally speaking that taboo has been broken. The real reason behind it was that the publishing houses didn't want to get to associated with any one writer, to be too dependent on any one writer. By the same token, comic strip syndicates were, and have always been fearful of the super popular cartoonist being all of their income. United Features' income is almost entirely the result of Peanuts. If Schulz left them, their income would collapse. He's stayed loyal, but he could syndicate his own work. He's made millions. He's grateful because they were with him when he started.

D: Even though they made him change the name.

B: Yeah, well. Other cartoonists just arbitrarily leave their alma mater in syndicates to go off and handle their own work. The guy who does Garfield is now more or less self-syndicated, and some of the others are going the same way.

D: What about Calvin and Hobbes?

B: It's being distributed by a syndicate. The wealth of a cartoonist is not necessarily related to the popularity of the strip. Schulz became a multi-millionaire because he decided to diversify into artifacts, toys of all sorts. Other cartoonists say that they will never do this. Walt Kelly, over the entire history of Pogo, only allowed three sets of Pogo toys, figurines, and worked on only two movie adaptations, otherwise he held off on all merchandising. There were no stuffed Pogo dolls. There were no endorsements of products or anything of that sort. Schulz will endorse anything, insurance companies, cereals. So that's a real source of income. In other words, it could be that Watterson might like to syndicate his own strip, but he might not have the where-with-all to do that. It costs a lot of money. Some other cartoonists attempted, on a very thin shoestring, to do it. Like Warren Tufts, who self-syndicated Lance. Because they don't have enough money, usually, to higher a staff, they quickly find out that the bedrock work of packaging up all those proofs, sending them out and keeping records gets to be unending. The money that they make from it doesn't usually pay for the time that they put into it.

D: Did Tufts go back to the syndicates?

B: No, after Lance he just sort of went into freelance, to make the obvious pun. He did comic book work and so forth. The guy who did Rick O'Shay and Latigo, Stan Lynde, is doing pretty well at it though. Both of those were syndicated by the Chicago Tribune, but he didn't like the way the syndicates and newspapers more or less forced his hand by demanding certain things he didn't want to do. So, he's now doing his own work up in Montana, publishing his own strip. It's not an enormous income but it's comfortable, and he can draw what he wants. Doing his own Latigo books and reprinting Rick O'Shay.

D: Which of those old guys have you met?

B: I've met Caniff, Mort Walker, and all those people. It's not so surprising since, after all, this is the Academy of Comic Art. I've met Will Eisner. He's practically a whole history of comics wrapped up in one man. He brought the comic book into the newspapers.

D: The Spirit sections in Sunday papers. Yeah, he was a real entrepreneur.

B: The whole concept of the splash panel, more or less, came from him.

D: You've got a whole taped interview with Roy Crane, right?

B: A long interview.

D: Will that ever get printed?

B: There isn't that much in it that's different from printed interviews. The guy that interviewed him, not me, tended to pretty much asked the standard questions, and he gave pretty much the standard answers back. We thought about printing it in one of the text accompaniments to the complete Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy but it didn't seem to be that much different from anything else.

D: Did you ever meet him?

B: No, never met Crane. He was around before most of the time that I was active. I've never even been to Florida.

D: I'm sure they have some big libraries.

B: Yeah, but not good newspaper files. The climate down there is hell on wheels for pulp paper.

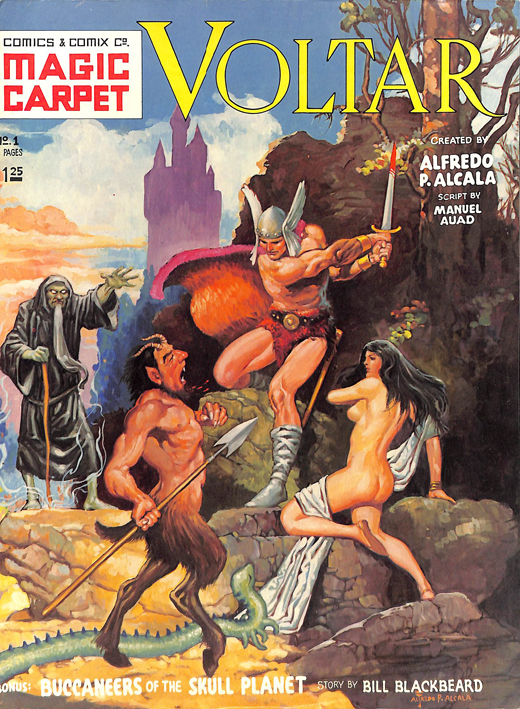

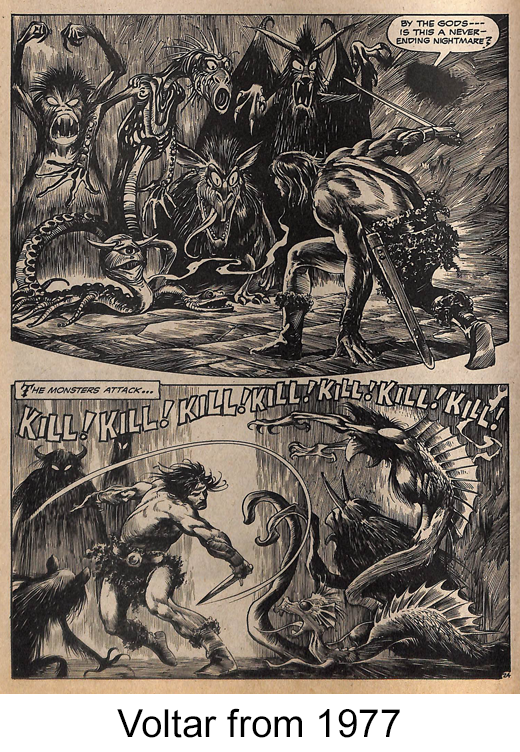

D: So how did the comic you wrote in the 70's, Voltar, come about?

B: (Laughs) The funny thing about Voltar is that it's not listed in the comic book price guide. The people at the Price Guide, because it was published by an underground San Francisco comic publisher, think of it as an underground comic.

D: They don't make any sense. Why can't that be in the price guide?

B: Because the price guide is very concerned about parental entry. All the comic books that they cover in there are at least technically clean. There's no sex, there's no filthy language in anything, so that they don't have to worry about parents saying, "My junior bought your Price Guide and now he's collecting Zap Comics. I never saw such filth in my life!" So they just cut themselves off from that completely on the strength that undergrounds broke all the taboos that were observed in regular comic books. The strange thing is that the same comic book Price Guide has references in its descriptive matter to things like "big boobs cover," "hypodermic needle cover," and that sort of thing. Apparently, that contradiction doesn't worry them. Their point might be that it was once published without legal action at some time in the past, so therefore it must be valid.

D: Back to Voltar.

B: At that time, I was mixing a lot with the people in the minor publishing levels around San Francisco before the development of the retail outlet comic stores. The underground people had ideas about getting into general newsstand distribution. They wanted to try some standard stuff. At that time Alfredo Alcala was more or less at loose ends. His time wasn't being totally commanded by DC or Marvel or any of the big houses. He was still getting himself established here. He had just come over from the Philippines a short time before. We got along pretty good, so I just did this goofball strip that involved linking the Cthulhu mythos to outer-space, nothing very new about that, and let my imagination riff on it. It was something that would be highly pictorial, that would give Alfredo a lot to work with. That's where Voltar came from. It wasn't my idea, they thought of a name that would look good.

D: Are there any foreign artists that you think are of importance?

B: Mostly I would say French or Belgians. Some Japanese people are quite good, but I don't know that field well enough to cite them. I'm impressed by what's pointed out in the work, but I don't follow it. In France and Belgium, you have strips like Tintin, Spirou and so forth. The body of people that came up with Metal Hurlant, which became Heavy Metal over here, like Moebius, who is wonderful. The great thing about the European field, particularly French and Belgian, is that you have a totally different comic strip structure, where you have a basically magazine format which serves as a source for what we would consider newspaper strip level material here. In other words, in the traditional comic book outlet in the past, American publishers would never have tried to market anything on the level of Spirou or Tintin, or a lot of the humorous adventure strip comics, because the juvenile American audience had been so totally corrupted by the superhero comic, they wouldn't buy it. That does seem to contradict the popularity here of such strips as Bone and Groo, where there is an audience for exactly the kind of thing that has predominated in the French and Belgian field. The general publishing staff at DC and Marvel will never believe it. I think they brought out Groo just to be a sort of a fun and games additional title. They were surprised that it did well.

D: I think Aragones was friends with all those guys too.

B: Sure. It'd also been sort of a success on its own as a pretty much self-published book. Same thing with Bone. Maybe it'll be printed by DC.

D: It was being printed in a Disney book.

B: That's a good start.

D: It sort of bodes well for the future. Maybe they'll see that not everything has to be a superhero.

B: It's funny that you would use "bode" since Vaughn Bode is another guy that falls into the same category. He was semi-underground.

D: But you're right, he was pretty popular. People/kids still ask for his stuff all the time. The graffiti kids especially, since he drew in that style… hell, he invented it.

B: Mark Bode is continuing it. I've got the Vaughn Bode archive that was given to me by his brother when he died. It's got his college work and all kinds of stuff.

D: You don't think that modern comics have gone down hill at all?

B: I think we are at a higher level than twenty years ago, in terms of the restrictions imposed. As far a crippling restriction, the newspaper comic strip field is an appalling wasteland. You can expand in certain very limited directions…

D: Do you think anything could break those down?

B: I don't think it will happen, but what would have to happen is a situation in which the newspapers might break away from the syndicated concept, as they are doing with the weekly papers, and begin to promote their own cartoonists. The SF Chronicle prints Farley, and other newspapers have had their pet local cartoonists, so that you do have a potential there. The thing that would really bring back the old comics would be exactly the thing that would destroy the present syndicate system and would impoverish two thirds of the artists, if you went back to large size daily comics of the sort that appeared in newspapers routinely in the 10's, 20's and 30's. Back to the time when you had four, five and six newspapers in every city, so that these strips were spread among all these papers. You could print the comics large and the cartoonists had lots of room to expand both graphically and in terms of story content. In those days, daily strips were routinely four and six panels, now they're three. Although Ernie insists on a four panel layout. You couldn't do all that now though, because there's only one or two papers in a given city. That means if you picked a few strips and ran them large, the other cartoonists would have no sales at all. You'd have a few cartoonists appearing in every paper. You'd have Peanuts, Calvin and Hobbes, Cathy and a few others that would be picked because of their demographics as much as their quality. All of the experimental or bizarre strips, including such strips as Ernie, would disappear. So, you can't have it anymore. In fact, the syndicates, by agreeing to, and pushing small postage stamp panel strips, saved the livelihood of most of their cartoonists, by pointing out to the papers that by using the much smaller strips you won't have to devote as much space to them and you can now run 20 strips a day, where in the 20's and 30's you only ran six or seven.

D: Most people read the strips first and yet they get this small scrunched down little section in the back.

B: There's nothing, theoretically, stopping papers from devoting four pages to comics and running them all big, but there are two factors that prevent that: one, of course, is the cost of newsprint, which has gone up again, but that seems to be countermanded by the very appeal that you're talking about. If comics have so much to do with the sales of papers, why not give lots of pages to the comics and then enhance the sales of the paper? Well, the other factor is the editorial staff, which despise the comics . If you go down to the Chronicle or the Examiner and talk to the editors and reporters, they will tell you that they don't read the comics. They think they are awful. They hate them because they know, in their heart of hearts, that the comics are selling a good part of the paper. They have to believe that it's their great news stories, their great exposes, their great dramatic presentation of news, their whole function in a classic mode of journalism, that gives them their professional dignity and status. If they thought they were playing second fiddle to the comics or to TV news... the chief barrier that keeps the paper from becoming a tenth or an eighth comics, is the editorial hatred of the comics that has prevailed ever since the beginning. Hearst had to fight this in his own newspaper all of his publishing life. They didn't want to run a lot of the comics he loved. They didn't like all of the comic content. The sports page editors hated the idea of a comic strip on a sports page. Hearst knew that people would go to read Barney Google on the sports page. Just as Captain Paterson of the News Tribune papers knew that people would read Moon Mullins on the sports page, that they would turn to the sports page to read them.

D: Are there plans for a Moon Mullins strip reprint in the works? Is there any interest by a publisher?

B: It's long overdue, but here you have that contradiction of even when they have great interest, they are still afraid of doing reprint books. Dennis Kitchen, for example, is a Gasoline Alley freak. He adores the strip, but he suspects that it would be a financial disaster. He's gone ahead and taken a plunge with Lil' Abner, but he says the book doesn't make him any money. He's supposed to go on with my Krazy and lgnatz series, yet for a year now he's had the entire book in hand, he's paid for it, my introduction, the layout, the art, the title, everything but it still hasn't appeared in print.

D: My last question is: How should people go about visiting the Academy?

B: Just make an appointment a day ahead. I wanted to point out the main purpose of the Academy aside from the newspaper aspect, is that we have enormous collections of popular fiction in the crime history, science fiction, detective fiction, sea fiction, pulp magazines, motion pictures and books on motion picture history. The thing that unifies all of these is basically the concept of the series character, that is the hero or anti-hero that's carried from book to book, from movie to movie, and from comic to comic, as well as the genre concept per say, the subjects. What we have here is the countries only cross-reference research library, where you can move from comics into detective fiction, from science fiction into motion pictures, following the trail of ideas, of character concepts, so forth and so on, from one genre to the other, all in the same place without having to go from one University's special collection all the way across the country to another University's special collection.

D: So, you think there is a lineage of say dime novels to underground comics?

B: Of course, the pulps went right into the comic books. The Shadow, Doc Savage and so forth. Recently you had a lot of borrowing from the pulps. Eclipse, before they went out of business was starting a Spider comic book. You had a G-8 comic book that came out from Dell. There was a Shadow comic strip that ran for four years.

D: Are there any dime novel characters that were continued?

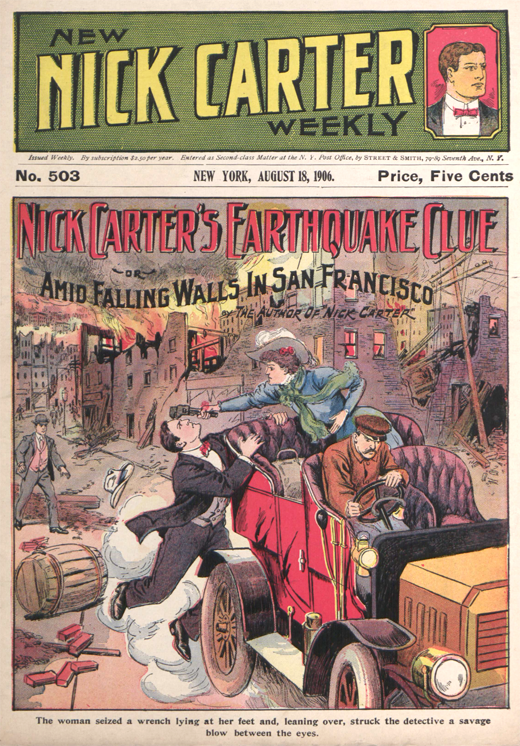

B: Sure, Nick Carter was not only a comic strip, it was a dime novel, it was a pulp, it was a motion picture. Walter Pidgeon played Nick Carter in the movies.

END