Comic books (comic strips) are now one hundred years old. The medium has changed a lot in that time. A lot of great things (Herge, Jack Cole, the heyday of the newspaper strip, etc.) have come and gone, as have a lot of bad things (Comics Code, low page rates, the assembly line, Vince Colletta, etc.). Change is a good thing, to a point.

We are nearing that point. When the printed text medium was one hundred years old, you had your Shakespeare. After one hundred years of comics we have lost nearly every great talent, in one way or the other. The ones that remain are fringe creators working mostly in other mediums or other countries (the Gary Panter Mall in Japan).

There are most definitely entertaining comics (From Hell, Dirty Plotte, King-Cat, etc.), but even the best of these is nearly invisible. The whole idea of doing great comics is nearly non-existent and rarely a goal. Second rate mediocrity has become a norm rather than an exception. Entertainment is a fine thing but when good entertainment replaces great art as a goal, what does it say of the medium and those practicing it?

This is not to say that all comic artists should aspire to "high"art and not entertainment. It is to say that modern comic artists must aspire to greatness rather than mediocrity regardless of whether what they aspire to do is art or entertainment.

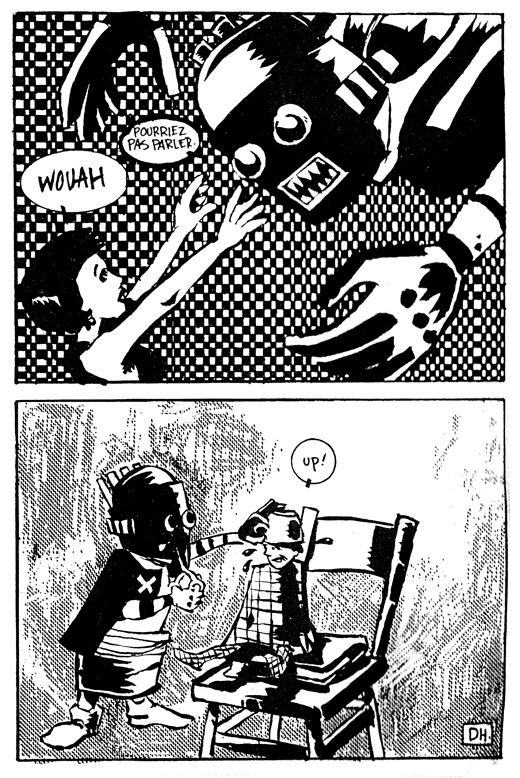

Often comic artists, out of a sense of inferiority to fine art/literature/film, aspire to "art" but only by taking what has become cliched and trite in comics (superhero, fantasy, etc) and applying surface art techniques to it. The end product is "painted comics," books like Marvels, Blood and the rash of painted hero books by artists like John J. Muth, Alex Ross and so forth. This work is still just the same inferior mediocrity only with a different wrapping. True art in any medium is only true art if it touches something in the view, inspires and makes us think, if it takes full advantage of the medium it's in. The painted comics of Lorenzo Mattotti are some of the few comics done with a directly color medium that should still qualify as art. There are of course, non-painted comics that fit this-bill.

Back to the main point. The thing missing from modem popular comics is one word: "great."

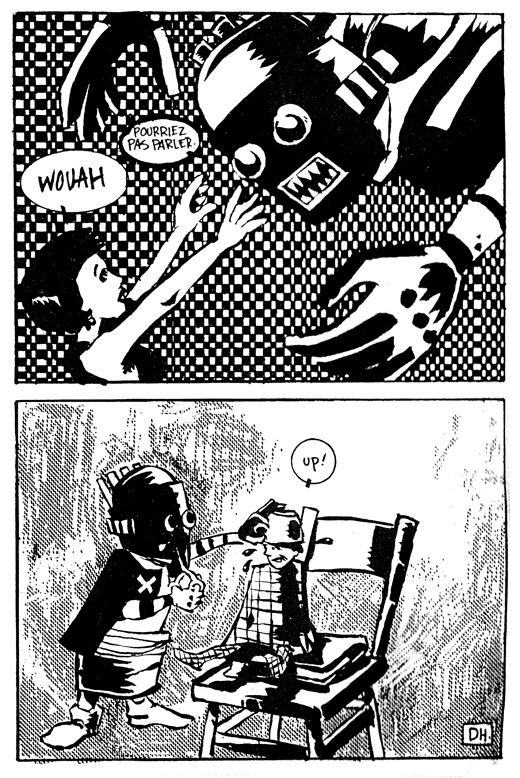

To be great, to do something great, to create great art, you must have one thing: "vision." Vision simply means that you see the potential of a medium and use it. The obvious modern example of this is comic artist Chris Ware. The surface style is interesting enough, but the great thing about Ware's work is that it could not be done in any other medium. When Ware's work is translated to computers (on the Wired web-site) people have decided to show it one panel at a time, thereby destroying the whole idea behind and integrity of his work.

Modem comic book artists like Dan Clowes, Jim Woodring, Chester Brown, Eddie Campbell, and maybe a handful of others all fall into this category. Unfortunately the work of even these luminaries sells so poorly that most of the major publishers would cancel them. The general audience reading comics is reading them simply for entertainment, for a quick escape.

How many times have I heard, "Oh, who cares? It's just a comic," or, "It's good, for a comic. It's better than most of the other comics out there?" Even I hear this stuff all the time, although most of my friends know this is the quickest way to piss me off (and make me go on ranting for hours). People seem to think that even the greatest comics can't compare to great literature, poetry, music or film.

This is the point of comics' greatest failure.

For the past fifty-plus years, comics as a popular medium have basically been a vast wasteland.

Admittedly, the medium has been ruled by finance and business since its inception... "Sell more papers." Money-making and creating lasting art are almost diametrically opposed to one another. The rule has always been, "Don't try to be Michelangelo," don't worry about making fine art just make the reader happy, to make money. From the beginning comic books were a way of making money from repackaged sure things (popular newspaper strips). The standard, however, was good work, even great work.

At one point, doing quality work was actually the best way to earn money in comics. There were bad, hacked out strips like later Ham Fischer's Joe Palooka, but to become a real star (and a millionaire, most often) your work had to reach out to the audience. People read Lil' Abner and stopped reading Palooka because it related to them, to the fact that they were human beings. Adults read it as they would a good book. Nowadays strips and comic books in the mainstream are a sterilized, hacked-out, pathetic carnival mirror version of reality, and sales continue to plummet.

Even with all the things that have changed over the last century, entertaining the reader and making money has remained the chief goal. Comics are judged as entertainment, for their popular culture appeal, much like Shakespeare or Dickens were in their own times. But over the last fifty years, standards have changed for the worse. For varied reasons there have been three major changes in the comics reader. 1) Their attention span is about 1/10th of what it was in the 1940's. 2) They have come to expect one or two genres at a time from the medium. 3) The standard of quality has become that of a fourteen year old white male suburban child. I would like to think that the old standards/types of readers are still there, they've just moved on to work/ entertainment that fills their needs (not the three above points). Only diehards remain.

In many ways the comic reader or fan has come to rule the medium and often create the work itself. As most of the money, fame and respect left comics, so did the talented master crafts-people. Work is now created by the third or fourth generation fan of that original craftsperson. An example follows of the degeneration of the "super hero style."

I should first say that I think the superhero isn't an inherently inferior genre (although many seem to think so). To prove this simply look at American tall-tales, the likes of Paul Bunyan, or Indian/Babylonian epics like the Mahabharata or Gilgamesh. The style for the example I'll use is the Alex Raymond (Flash Gordon)/Hal Foster (Prince Valiant) illustrative style. Both of these two greats were extremely influenced by the style of great illustrators like J.M. Flagg, Howard Chandler Christy, Joseph Clement Coll and such, their writing by classic hero fiction of the times. From their influence Raymond and Foster arrived at a new point and imparted their own adult vision to their work. In turn, a number of creators in comics saw their work and took inspiration from it. Some were unique visionaries like Lou Fine and the artist/writer team of Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, and some were mid-range hacks like Shelly Moldoff. The visionaries' work stood out and was aspired to by the next generation, Gil Kane and the artist/writer team of Neal Adams and Dennis O'Neil. By this point (the 1960's) the three earlier points had already come into play but some vision and personality remained, but for most of these people, their vision stopped where the paycheck began.

The reader had to feel good about reading comics, but the audience, like the creators, still expected a modicum of quality and vision. Soon the next generation began to emerge, artists/fans like the artist/writer team of John Byrne and Chris Claremont, Michael Golden and Mike Grell. They in turn influenced 80's artists like Art Adams and Jim Lee, and they in turn are influencing the new crop.

At a certain point, the process became slavish imitation rather than inspiration. At certain points, new bits of originality are/were introduced (Neal Adams advertising art influences or Chris Claremont's TV references) but most of these said little or nothing of their individuality. Sometimes individuals like Alan Moore or Frank Miller would be brought into the mix (Miller was a fan of Bernie Krigstein who in turn adored Simon/Kirby) and bring in a heapin' teaspoon of personality. Unfortunately, that is like adding a shot of whisky to a pint glass of water.

The field of comics is like any other and is judged by its most public and (in our capitalist culture) money-making face. People looking in at comics see Jim Lee's Wildcats as the success and Jim Woodring's Jim as the failure.

Admittedly there are currently much finer comics than the Jim Lee ilk. Some like the Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman side remain relatively successful. Both of those artists do descend from the lineage of great artists like Walt Kelly and Chester Gould, and continue to inspire great work from the likes of Joe Sacco and Chester Brown. Unfortunately these artists (Crumb and Spiegelman) aren't the standard and Jim Lee is.

In a medium where the standard of quality and success is a preponderance of inbred high school level artists who approximate the technique of a fifth generation Alex Raymond, where does skill fit in? It doesn't! Unfortunately, skill and quality are for the most part, judged, even by those of us on the outside track, against the work that sells. I mean, the number of times I've heard, "Neil Gaiman is a great writer," or, "Matt Wagner's art is amazing" is beyond counting. Even the likes of Chris Ware, David Mazzucchelli and Mark Beyer are compared by reference to the Jim Lee, Alan Moore, and Frank Miller standard. This standard falls to shit if you introduce David Mamet or Paul Auster. Chris Ware and his bunch still hold up though.

I propose that now is the perfect time to change the standards back. The change that is taking place in the comic book industry as I speak (with distribution, etc.) is a perfect chance. A rift has been created within comics between the people who see comics as a grand medium and people who see it as escapist genre fiction that has made it hard to apply one standard for all comics. I propose that the only way to create a new high standard for the medium of comics, is to completely change the standard, to make "good" into "great." To replace Bone, Hate and Teenage Mutant Turtles with Acme Novelty Library, Eightball and Peanuts.

It's just a shift in ideals. One of the best ways to affect this shift is to stop doing comics any favors. Compare work in comics by ourselves and others to great work in any other medium. Whether art or entertainment is an end, comics are about communication, so they can, and should, be compared to work in any other medium of communication. Quit saying things like, "It's great...for a comic." Entertainment is fine, but there's never any excuse for crap.

At a period crucial in the development of the medium, when artists and critics are beginning to reach unparalleled heights in the use of the medium, we must stop judging work by these horrible standards, or the work will stagnate or leave comics in search of higher pay and greater recognition. Of the entire flock of Raw artists, how many continued to push their comic work? Was there a reason for them to?

Comics as a medium aren't 6" X 10" saddle-stitched twenty-four page superhero or autobiographical stories. One of the greatest lessons from the Raw artists (Chris Ware, Spiegelman, Burns, etc.) is that there is no set formula for comics in format, style, genre or technique. Unfortunately for comics as a whole, we weren't ready for the lesson. It fell on deaf ears. In grand comic fan/ artists' tradition, the response to Chris Ware is, "Wow, look at the way he does that!" not, "Wow, I can do anything I want with comics." The end result, much in the way John Byrne related to Neal Adams, is the Al Columbia story in Zero Zero in the August 1995 issue, just a bad photocopy of Chris Ware.

To use a great quote from Howard Chaykin (who is his own best example), "Being the best comic artist today is like being the world's tallest midget." By best, he meant the most popular /highest selling comic artist.

Even as a reader (fan?!) of comics, why support crap? Why endorse it? Compare what you expect from your comics to what you expect from TV, music, film, books, whatever. Why the fuck would somebody who only narrow mindedly buys indie label music; buy a comic by Time/Warner (like Sandman)? They do though, and a lot of them. What does watered down crap like Cerebus or Stray Bullets offer to a fan of Twin Peaks or Taxi Driver? Demand quality and intelligence; don't let your entertainment insult you.

The burden of the blame cannot rest on the reader. It must lay with the producers. The reader can only choose from what is offered. The blame lies with the critics, creators and historians. The critic must stop being a "company" man: "I like anything Drawn and Quarterly does." The critic must judge work by the highest standard, not the current trend. The critic must fuel the creator to create work of the highest standard.

The creator owes it to the past, present and future artists to produce their best work, while aspiring to greatness. The quality of work produced in the past is a heavy weight indeed, but if you don't find out what's gone before, you will be doomed to repeat it. Don't slavishly copy it either. Draw inspiration from it. Who wants to see another Wally Wood or Frank Frazetta hack like Mark Schultz? What the hell does that achieve? Modem artists all need a kick in the ass, and pushing yourself does that. If you don't push yourself, the next generations will only get worse, and the medium may die before you do.

Lastly the weight of producing good work nowadays lays with the scholar and historian. In many ways some of the most important work in comics in the 80s was the amazing amount of reprints. Many of these books (published by NBM, Dragonlady, Fantagraphics strip reprints, and Marvel and DC classic reprints, as well as books by Eclipse and a number of other black and white publishers) will not be seen for their full importance for years. Unfortunately, thanks to the idea of the "fan" replacing the scholar, the recent research and documentation of the history of comics lays in the hands of six or so men. Try reading the average interview with, or article about, say, Bill Everett, and you'll find out anything you'll need to know about the Sub Mariner, but next to nothing about his use of color for Atlas comics in the 50's.

Now is a great time to do great comics, there's no one to tell you that you can't.

My points are simply these:

- Stop inbreeding

- Push ourselves as artists

- Judge all art/entertainment with one common standard

If we do these few things I honestly believe comics as an important medium will have a future, if not, the preponderance of crap, and death of the artform will be complete.

My reasons for all this are simple, simple and selfish: I worry about having readers for my work. The future of comics seems frighteningly bleak, but I think there is a ray of hope.

So there... go do something great.

[Originally published in Destroy All Comics V.2 #4, January 1996]