Seth is the creator of the comic book Palooka-ville, of which six issue have so far been released. Dylan Williams interviewed him over the phone in January 1995.

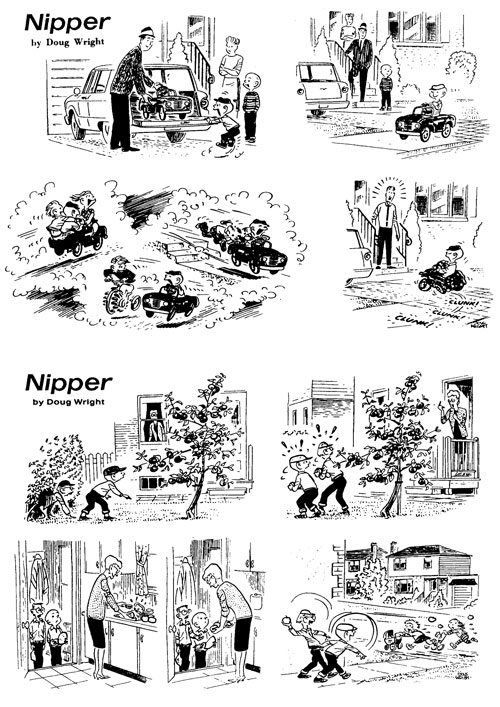

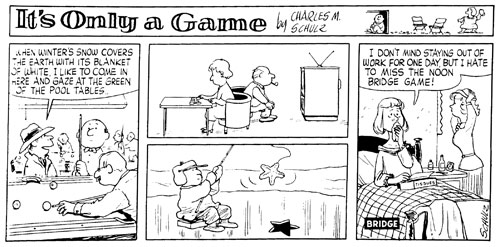

Seth: My very first influences in comics or cartooning, the first things that interested me in it, would be a combination of a few newspaper strips. The first would be Peanuts, of course. Peanuts has been a lifelong interest, and I don't think a point will ever come where I don't love it as much as I do now. Around that same time, there was a Canadian editorial cartoonist who signed his work Ting, although his real name was Merle Tingley, who came to my school when I was in grade one or two, and gave a little lecture, and after that... I think I was always following his work anyways, because like a lot of editorial cartoonists he had a little mascot creature in his drawings that was a worm! You had to look for it in the cartoon, so that was enough to make me interested in it when I was that young, 'cause obviously I wasn't interested in the subject matter. He really inspired me and made me see that people were cartoonists, that there were actually people doing this. That, and my parents used to have certain strips they really liked, which I mentioned in Palooka-Ville. Like Nancy and Andy Capp, that my mother really liked, were real big favorites of mine, and still are, and this strip called Little Nipper, by Canadian cartoonist Doug Wright, was another thing that I still think is a great strip. These things were probably the first things that got me interested. Like any kid, I was reading a few comics at that time, I was reading Heckle and Jeckle, and Richie Rich and Archie's and stuff, and...

Dylan Williams: Did your parents have any anthologies of the cartoonist's work, or did they just get it in the paper?

Seth: Just from the paper. There were a few paperbacks around the house, but the truth is, there weren't ever many books around my family's house. I think my interest in reading and cartooning, is something that really just sprang … I don't even know how it came about, except that I liked the stuff. Because there was no tradition in our family towards the arts in any way, like nobody in my family even was much of a reader.

Williams: Did you get the New Yorker?

Seth: No, my family was definitely lower middle class. At one point or another, we were even living in a trailer park. So, definitely as a young man I wasn't flipping through the New Yorker, or the New York Times or anything. My dad was a mechanic when I was really young, and later he was a shop teacher. I've got to give him credit though. He had a grade three education, and he managed to up it, and go back to school and go through teachers college and everything, so in retrospect, it's kind of impressive.

I remember sometime in grade school, actually it was at summer camp, I read some Marvel comics. They were Kirby X-Men. They were in a big box, so they hadn't just come out or anything, and this fired me up. This really got me interested in comic books in a way I'd never been before.

Williams: It's funny, when I think about Kirby stuff, those are the ones that I think are the least great, but even then they are so great.

Seth: When I look at those, I still have all of them around here somewhere, that stuff just looks great to me. There's a real nostalgic charm to it that's unmistakable. It's really appealing to me. For some reason that got me fired up, and when I got back home, I remember I started watching the Spiderman cartoon on TV and stuff, and then I remember, it kind of clicked together one day, "Hey, Spiderman's in a comic book," so I started buying comic books, and within a few years I was a total Marvel addict. I went through this period, through most of my teen years, of buying and reading every single Marvel comic that ever came out. That's where I developed my drawing ability. If I hadn't loved comic books, I wouldn't have spent that much time drawing. I think it's probably true of an awful lot of people who do comics, since the fact that they were kind of an outsider to the scene, I was definitely a loser in high school. If they had a drawing ability, they would produce their own comic books. I must have drawn hundreds of comic books when I was in high school, all superhero crap, and some horror stuff.

Williams: There should be some therapy group for kids like that.

Seth: To keep them from ending up at Marvel. I see some groups for those kids, but they don't look too good. They're role playing groups in the back of a comic shop or something. I was fortunate that I didn't know a single other person who read comic books until I was in my twenties. I was horribly ashamed of it, in fact, so there was no way I was going to tell anyone in high school that I was reading comic books. I figured, "I'm enough of a loser, I don't need to add this to the group. They have plenty of reasons to hate me as it is." But that's where I think I really developed my drawing abilities. If it hadn't been for that I probably wouldn't be able to produce a comic book now.

I guess it was around when I went to art school that I lost interest in those Marvel comics, but I still had interest in the medium.

Williams: And you were just doing painting...

Seth: Sure, yeah, I was in a more commercially oriented department...

Williams: Were you in illustration?

Seth: I was in what they called communication and design, which incorporated any kind of artwork that was for commercial purposes. I took illustration courses, and I took graphic design courses, and production art, and technique. All those things. But half way through art school, I really realized, ''This doesn't do me any good. At the end of this I'm going to end up working on the Jell-O account or something, this isn't going to make me a cartoonist," so I kind of got disenchanted with the whole thing, and that's when I. ..

Williams: So you still wanted to be a cartoonist?

Seth: Yeah, even during all this I still wanted to be a cartoonist, I just didn't know what the hell I was going to do with it. I was really kind of mixed up. There's only been one point in my whole life, since I was a kid, where I didn't think I was going to be a cartoonist, and that was in my third year of art school, and I was really fucked up, and I thought, ''This ain't going to happen. This is a dream. '' I guess this actually would have been right after I dropped out of art school, because I hadn't even drawn anything for about eight months, and I thought, "I'm not going to be a cartoonist. I'm not going anywhere. I'm working at a shitty job, and I'm not doing any art, and what was I thinking anyway, I don't even know what I'm going to do."

Williams: What kind of job was it?

Seth: I was working in a jewelry factory, assembling costume jewelry. And I was also really fucked up on drugs at that point too, so life really didn't seem like it was heading anywhere.

Williams: So, how much art school did you have?

Seth: I was there for about two and a half years.

Williams: Did you learn all the basics of drawing?

Seth: I guess so. I start to wonder what you really learn in art school. It's a good place to kill time.

Williams: It depends on the teacher. If the teacher is really teaching you stuff, then it's important, but if it's one of those, "draw how you feel," kind of things…

Seth: Yeah. First of all, I think I was too young when I was there. I just wasn't prepared to learn. The truth is, I didn't really have a clue. I remember being in graphic design class, and I didn't even know what graphic design was when I was nineteen years old! I would look at the stuff, and it would seem like some sort of a magic thing to be able to get a graphic design that you would get an A on. I didn't know how it worked. Now, it's like an instinctual thing. You look at something and you can tell what's good graphic design and what isn't, but at that point I was completely lost. I was an idiot, and I didn't learn anything really useful when I was in art school. I feel like most of my learning has come through self-teaching, because you have to learn when you're ready.

Williams: I really think that most art school is a fraud because nobody is really ready to sit down and learn that stuff when they're nineteen.

Seth: Exactly.

Williams: You have to be like twenty-five, or you have to be mature enough to actually digest the stuff.

Seth: I mean, what the hell do you know about anything when you're nineteen, and how can you translate that experience into any sort of an artistic statement. It's pointless. I think the best thing you might get out of art school is a lot of life-drawing classes. That was always fun. I don't know if it helped my drawing, but I sure enjoyed it. It's always a pleasure to draw from the figure.

Williams: Yeah, I agree. If you sit down and actually look at things...

Seth: It's definitely something every cartoonist should do.

Williams: I spent three years straight, all the way through the summer and everything, just going to figure drawing classes.

Seth: It's definitely important, because you really can't learn to draw from other cartoonists.

Williams: Despite what Todd McFarlane said.

Seth: You can learn to emulate their stylistic ticks, but it's not going to help you draw any. When it really comes down to the basics of drawing and composition, you can't learn that from anybody else. You've got to learn that yourself.

Williams: What renewed your Interest in cartooning?

Seth: I guess when I was about twenty, when I was in art school, I pretty much lost interest in cartooning, for a while. That's because I stopped reading the Marvel comics. I was still interested in comics, but I just didn't realize there was such potential to the medium. So for a couple of years there I just stopped doing any kind of cartooning. I was just goofing around. I dropped out of art school. I started doing a lot of drugs and stuff, and then, I read an ad that Vortex Comics was looking for an artist or something. I went up there and showed them some stuff that I had and they didn't care for it, but this guy Ken Stacy ... I don't know if you've ever heard of him...

Williams: The airbrush guy.

Seth: Yeah. He took me out to the comic shop, because I told him I wasn't reading any comics and he said, "You gotta buy this Love and Rockets." So this would probably be '82 or '83, and so I picked up issue number three and I started reading Love and Rockets. For a while that's all I read, then I started branching out and reading some other stuff. I was picking up Chester's minicomic Yummy Fur, and...

Williams: Did you know Chester then?

Seth: No, I didn't. I wrote him a letter sometime around then, and that's when we made our first contact. We didn't really meet until we both worked at Vortex a couple of years later.

Then I started to get interested in comics again, and started to read some of the undergrounds I'd read as a teenager, but didn't really understand. I started to pick up on Crumb, and started to dig more deeply into the alternative comics scene. I started reading Weirdo and Raw, and stuff like that.

Williams: Was that stuff available at any store around there?

Seth: Yeah, it was actually pretty easy to find here in Toronto. Toronto is not bad for... the Beguiling wasn't open yet. Which, in my mind, is probably the best comic shop I've ever seen.

Williams: That's what everybody says. Except Quimby's, which sounds like it's pretty close.

Seth: I haven't heard much about that, but there were a couple of comic shops here that were pretty good. There's a place called the Dragon Lady that had a lot of old stuff, and there was a place called the Silver Snail that carried a fair amount of alternative stuff at that time, although it's pretty much a mainstream store now. But, it was easy enough to find this stuff... American Splendor and things like that, so I got my interest in cartooning revitalized around that time, and that's when I ended up drawing Mr. X.

Williams: There was some other comic that somebody told me you drew for Vortex.

Seth: I did a bit of stuff in their Vortex magazine. They had an anthology title, but besides that I didn't do anything for them but Mr. X.

Williams: What did you feel about doing the Mr. X stuff?

Seth: In retrospect, I didn't have any moral qualms about it. Looking back on it, I probably should have had some moral qualms about coming on after the Hernandez Brothers, after Bill had supposedly screwed them around, but the truth is, I didn't really know anything about that at that time. I'd just started reading the Comics Journal, and by the time I was working on Mr. X it wasn't common knowledge that Bill had screwed them around. I suppose I should have made some sort of a moral choice after that, but I just stuck with it. As an esthetic choice, at that point, I didn't really have any esthetic problem with Mr. X. Not until I'd been working on it for a while. I really liked what the Hernandez Brothers had done on it. Looking back on it now, I can really see that the stuff they did on it was really second rate compared to their Love and Rockets work, but at the time it seemed great to me. So, I was happy to get the job at first.

Williams: Great by regular standards too.

Seth: Yeah, exactly.

Williams: The best of the schlock.

Seth: Yeah. So, by the time I left the book it felt like I'd made a major mistake working on it. The only thing that I can say really good about it is that it forced me to draw a lot, and develop my style a bit. Whenever I look at those Mr. X's, which is almost never, I can really see that I was learning to draw better through them. From the beginning to the end it's a real inconsistent bunch of comic books. At least it prepared me for what came later. But if it was now, I certainly wouldn't be taking on a project like Mr. X.

Williams: Have you ever talked to David Mazzucchelli, because what you're saying there sounds like what happened with him too.

Seth: Yeah, I guess so. I've only met David Mazzucchelli once and it was for about two minutes, so we didn't really have any time to talk. It seems like sort of a miracle to me that he got out of that world. He's the only one. I don't know anybody else who has gone into mainstream comics, real Marvel/DC, and ever come out to produce anything worthwhile.

Williams: Really it's the opposite. There are all these underground guys who are now ending up working for Marvel and…

Seth: Yeah, that's sad.

Williams: It's horrible.

Seth: I just think those places soul destroying. You can't go in there when you're twenty years old, and then five years later, after doing that, come out, and still have an artistic vision. It just warps you. You're surrounded by all these people who think the same way and have the same interests, and I think you probably get sucked in, like any kind of a corporate structure. I'm sure that if I'd gone to Marvel Comics at nineteen, and they'd said, "You can draw our books," I'd just be a hack now, 'cause there's no way you can survive it.

Williams: I think if you have a strong enough vision, like with Mazzucchelli, I think that's what it is. His vision is so intense.

Seth: His old friends there must think he's nuts.

Williams: Actually, he has this great story about Rob Liefeld looking at his stuff and going, "What happened to him? Oh my God! This doesn't make any sense."

Seth: I believe it. They must just think he's a kook.

Williams: Which is great!

Seth: Yeah. Well, considering none of those guys can draw, they're certainly nobody to be judging anything.

Williams: Did you have a lot of freedom on Mr. X to do stuff, or did he just, I don't know… I haven't even read those actually.

Seth: Well, don't bother. Yeah, I had a lot of freedom. The guy I worked with, Dean Motter, who was the writer, he would basically just give me the dialog for the book, and I would just break it down, and design the characters and whatever. But even so, it's not a satisfying experience even when you have that much control. You're not writing it and you're not coloring it, and they won't even let you do the cover. It's kind of soul destroying too, when you're drawing the book and they say to you that you're not good enough to do the cover. It makes you wonder, "Why am I good enough to draw the insides of the book, then?" Ultimately, I just don't believe in working with writers anyway. I think it's a pretty rare exception when that works out.

Williams: If there's a collaboration, isn't…

Seth: I guess that's why I have this opinion. I can't collaborate, so I judge everything from that. I find it hard to imagine ... I suppose I could collaborate with Chester, but then I often think, "but, what's the point?" Both of us can just do our own work. We don't need to get together on anything. It's rare for me to find anybody that I can enjoy working with that much that I'd ever want to collaborate with them.

Williams: I'd like to see you and Chris Ware do something.

Seth: That would be interesting. I just can't imagine it.

Williams: How did you get into illustration?

Seth: That was a plan on how to get out of comics, so I could do my own comic. When I left Mr. X .. I had a friend Maurice Velikoop... you've probably seen his work in Drawn & Quarterly, well, he's a big illustrator, and I could see he was making a lot of money. I thought to myself, there's no way I could work on Mr. X, for example, and do a comic book of my own on the side. It's just too much work. But I thought if I did illustration, I could make more money for less work, and still manage to get my comic book out on the side. But that really didn't work out too well, because for the first couple of years of illustration I had to work so hard to build up any sort of a career, that I was working seven days a week on illustration.

Williams: Was this before Palooka-ville came out?

Seth: Yeah, this was the couple of years in-between those two books. So, finally it was so busy I just had to say, I'll have to schedule my time better and do less illustration, and get the comic done. So basically that's what I've done now. I just take as much illustration as I need, and just use the other time on the book. Ultimately it worked out, but for the first couple of years ...

Williams: Do you have people coming to you for jobs?

Seth: It depends, it's really hot and cold.

Williams: That's what makes me never want to do illustration. Every time I've tried to, I have a great job for a week, then after that it's dead for the next month.

Seth: It's scary being a free-lancer, but I've had steady work for the last five years. There's been some points where I've been down to my last buck, and I'll get scared and start thinking, "I better find a representative, or something," because the works drying up, but then some more always comes. The recession was kinda tough, because illustration really dropped, but the last six months, or whatever, it's been really good. I've been getting lots of work and I've been able to have enough money to take a month off to work on the comic, and stuff like that. So, it's been pretty good lately, but I'd like to get out of illustration.

Williams: Where have your illustrations appeared?

Seth: Well, they appear mostly in Canadian magazines.

Williams: Like travel magazines, or stuff like that?

Seth: Lifestyle magazines, newspapers. I do a lot of work for one of the newspapers here in town. In lifestyle magazines I do a lot of restaurant illustrations. I've done work for New York magazine and the Washington Post. I almost did some work for the New Yorker this year, but that didn't work out. I did a cover for them, but it ended up getting killed.

Williams: For the New Yorker?

Seth: Yeah.

Williams: Wow.

Seth: It didn't see print. It was pretty disappointing for me because I was really looking forward to seeing it on the cover, but it didn't come through.

Williams: I'd think they'd see your style and go, "This guy is for us."

Seth: I'd like it, but... they sent me a thing telling me all the new holidays coming up, if I want to submit some ideas, so... we'll see. I was pretty bummed out when the cover didn't see print, so I've got to build up my enthusiasm again, to try to work up some ideas.

I don't really like their system. They send out these newsletters to everybody. So you've probably got like fifty people competing for that Valentine's Day cover, and they probably just pick the best one. I prefer the old the old commission idea, when they call you up and commission you specifically.

Williams: That's treating it like art. They don't want to do that anymore.

Seth: Yeah, well, I just wanted that big fee too. They pay very well.

Williams: That's what I hear.

Seth: But once you get in, it seems like it's pretty good. People like ... who has been doing covers lately a lot... well, certainly Art Spiegelman has.

Williams: David Mazzucchelli’s done a couple.

Seth: Yeah, Mazzucchelli really seems to have his foot in the door now. I must have seen like three or four covers by him so far.

Williams: There's a Mattotti cover on the new one.

Seth: I think he's already done a cover for them, so that would make sense. And I've seen Zingerelli ... quite a few cartoonists are doing stuff for them now, which is good, 'cause that's like the old tradition. I prefer that than getting illustrators to do the covers.

Williams: Yeah, Evan Dorkin has a theory that with comic artists getting more illustration jobs, that it's maybe gonna open people's minds up to comic books.

Seth: I think he's kidding himself…

Williams: Nothing will do it.

Seth: Yeah, I'm pretty cynical about that.

Williams: What makes you chose the specific events you write about? Is it that they just stick In your mind and they keep on coming up?

Seth: You mean like the specific events within the story, or the different storylines in general?

Williams: The different stories in particular. Are they things you want to deal with, or are they just unresolved issues?

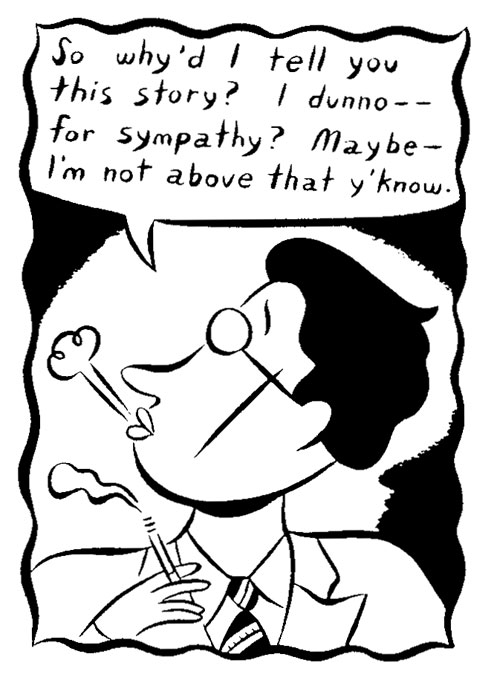

Seth: For the first three issues, I look at them really differently than from issue number four on. Especially with the first issue, I feel like, this was my first comic story, and I think I made a fatal mistake. I picked something which is like a good anecdote, which is the kind of thing you might tell to some friends, to get some laughs or whatever, but a good anecdote very rarely makes a good story. I don't really feel like I knew what I was doing with the first issue.

With the storyline that started in the second issue, that ran in two and three, I felt like I had a better grasp of what I wanted to do, but I still didn't really know how to pull it off. When I look at that story now, I see that it should have been at least six issues long, and I should have paced it really differently. But, I had to do those to learn, first. Starting with issue number four I really felt like, "Now I know what I want to do and how to approach it." The way I look at it now, I would pick a story that has some potency, beyond being just something interesting that happened to me. This is kind of my complaint with a lot of autobiography, like what Dennis Eichhorn does, for example. It's too much of, "Here's some weird shit that happened to me," and there's not any real introspection attached to it. I feel like there has got to be a point in telling a story. Obviously, or then there's no point in telling it. So now, I would pick a story more for what I want to say with the story, rather than with the specific events of it. In my mind, the events are secondary.

In "It's a Good Life If You Don't Weaken" the search for Kalo is more of a catalyst for the story. It's just the motor that makes it run. To me, it's not the most interesting thing about it.

Williams: What's the most Interesting thing about it?

Seth: The most interesting thing would be, my underlying points of what I'm trying to say about life. Which will involve why Kalo is in the story, but it has a lot more to do with basically trying to explain how I feel about the world, and that's just the plot to build it around.

Williams: That's a big point for a lot of cartoonists, when they start realizing there should be a purpose…

Seth: Yeah, exactly. So much of cartooning has had to do with entertaining, and because of that I don't think most people come to the medium thinking they have to have something to say. They just think they have to manage to entertain people. So you get into this whole thing where you do one or two page stories, and if you get somebody to laugh, that's good. They never really reach that point where you really have to say something, which of course, is the most important thing if you're going to be a writer of any sort.

Williams: Yeah, most people don't approach it like it's writing.

Seth: Exactly. You've got too many people who've definitely spent too many years working on their drawing. They didn't realize they had to work on their writing too. It certainly happened to me. I mean, I'm thirty-two years old, and I'm just figuring what to do with the writing now, I'm just starting to figure it out.

Williams: When was the stuff in Drawn & Quarterly, in relation to Palooka-ville?

Seth: I think the first thing I had that appeared in Drawn & Quarterly came out before Palooka-ville, and then the next stuff probably came concurrent to the first couple of issues.

Williams: So that's probably the first thing you'd ever written?

Seth: I guess I wrote a couple of really crappy things in that Vortex Magazine, and I guess I did a couple of one page strips here and there, before. But, I would probably put that as the first stuff I'd be willing to admit to.

Williams: It's interesting to see a progression in artists.

Seth: It's always more interesting to see from the other side, but it's pretty painful to look at your own early stuff.

Williams: Oh yeah.

Seth: But, it never bothers me to look at early stuff by other cartoonists that's really bad. I think it's interesting.

Williams: Personally, I'd kill to get any of the stuff Charles Schulz did before Peanuts.

Seth: The Little Folks. I've got the teenage stuff.

Williams: You've got the Little Folks book?

Seth: No. No. Actually, I was thinking, in my next issue of Palookaville, I was going to put a request, if I have anybody who lives in Minneapolis/St. Paul to Xerox that stuff off the microfilm for me, and I'd gladly trade them some original art for it, because I'd really like to get my hands on that. There's two years worth of it.

Williams: I can see if Bill Blackbeard has some, 'cause he might. He doesn't really like the early stuff. It's funny, I was having this conversation with him, where he was complaining how bad it was in the first couple of books.

Seth: I love that first couple of years.

Williams: I know, it's totally... That's a perfect example, like Schulz isn't proud of it at all. He thinks it's bad, so he's not going to reprint it at all.

Seth: Yeah, I was reading an interview with Schulz about a year ago where somebody was suggesting that he turn Lil' Folks into a book, and he was like, "Nope. Nope. I don't want that to see print." And it's too bad, 'cause I'd like to get my hands on it. I think the drawing was really beautiful too. It's definitely a different animal that early Peanuts stuff and the Lil' Folks, than the later Peanuts stuff, but it's still nice. I like it.

Williams: That's why you should reprint your early stuff in one book.

Seth: Well...

Williams: Do you think about people not relating to you work at all? It's an issue to me... I do this stuff, I'm really interested in the 50's, and people don't relate to it at all, because It's not autobio, and it's not this, or whatever.

Seth: I don't think about it, because I don't think I really have that much connection with my audience, that I'm ever talking to them personally or anything. I get letters from people, and usually, you just get letters from people who like what you're doing. I don't know. Joe and I have talked about this kind of thing, 'cause I think Joe is very conscious of his audience. He's aware of them. I don't think about it that way. When I'm writing the comic I just think, I pretty strongly just think, write what you want to read. I assume that my audience is smart enough, I could be over-estimating them, but, to overlook these lifestyle differences. Sometimes I'm aware of it. I think, "Here, I'm insulting these trendies, they might be part of my audience and they might be pissed off," but I think, "You know, that's life."

Williams: Yours is the first comic I've read where I actually felt some kind of identification. Normally, like I read Joe's stuff, and I think he's a jerk, but his stories are always great, so I'm really interested in it, but I don't identify with his lifestyle, but with you, both Jeff LeVine and I, we can relate to the idea of going to a book store and pouring through these racks of stuff, just to find this one thing that nobody else would care about.

Seth: I appreciate that, and I'm surprised to find out that most of the letters I get are from people who say they relate to that.

Williams: Wow.

Seth: So maybe there are more like minded people out there than we think. Who knows? But yeah, I usually don't assume that the audience is going to relate, 'cause I feel kind of like an oddball sometimes.

Williams: But, it's just that you feel like you have to do it.

Seth: Yeah, exactly.

Williams: Crumb talks about that too.

Seth: I really related to Crumb when I was younger, especially, I remember that story, That's Life, where he's lookin' for the old records. That really struck a chord in me when I was about twenty-two. I don't feel that Crumb influenced me, but I feel that when I first read Crumb, there was that feeling that he confirms your own thoughts ...

Williams: You don't feel so crazy.

Seth: Yeah, and I really did feel that his interest in old time things made me feel a certain confirmation that this wasn't a weird interest.

Williams: Are you aiming your story, It's a Good Life ... at other cartoonists?

Seth: I guess that's in the back of my mind, but part of me ... I'm thinking, I've seen plenty of movies about film directors, and hundreds of novels about authors, and I feel like I can relate to that. That's why I put the glossary in there though, because I figure, I don't assume the audience knows who I'm talking about, but it doesn't really matter. It's almost incidental if I'm talking about a cartoonist, what's more important is whatever point I'm trying to bring up about life. I'm just connecting it to cartooning because that's the way I am. I figure it's a good enough metaphor, 'cause Salinger can bring in haiku if he wants, so I figure I can bring in...

Williams: Hergé.

Seth: Exactly. I assume that an audience reading comics has some interest in cartooning, so they should be able to relate.

Williams: It's worked on a lot of people. I work in a comic book store, and they're interested in these other people 'cause you mention them.

Seth: That's good. I'd really like to think I'm turning on somebody to some artist or another.

Williams: That's my goal as an artist too… to make people aware of these older people who were so great.

Seth: Sure. There really is a ton of great cartooning out there, and it's a real shame that most cartoonists don't have much of an interest in it.

Williams: In the story where you're showing Chester, I totally identified with that. I have so many friends, I'll show them this great comic and they'll be looking at the ad pages or something like that.

Seth: You know, like I said, I think people have been trained to look at the past through the eyes of kitsch and it's hard for them to see the quality of things that aren't new and hip, unless it has some sort of a trendiness attached to it. Like suddenly the seventies are hip, but if it wasn't hip, I don't think anybody would be looking back at the seventies looking for any real quality or anything. And they're not bringing back anything from the seventies that were quality, they're just bringing back kitsch stuff, and I think that's the way pop culture operates. You can only appreciate things through a sort of ironic looking backwards, and that's bullshit.

Williams: "Wasn't it stupid that they did this, and funny, ha ha."

Seth: Exactly. Instead of seeing that some things in the past might have actually been superior. Certainly, looking at cartooning, you see an awful lot of evidence that things were better in the past. Like the newspaper strips for example. Such great strips. When you sit down and read a huge run of Little Orphan Annie...

Williams: Actually, that's the next thing on my list after this huge pile.

Seth: Once you get into it, it's so engaging. Harold Gray might be kind of right wing, but his actually storytelling is terrific. It's really fascinating stuff.

Williams: I think it's neat. Even if I disagree with the politics, or all that of the artist, it's really interesting to me when people are really opinionated. Because otherwise it's just bland and boring and lifeless. Like Steve Ditko, I don't know if you like him...

Seth: Sure, I love Ditko.

Williams: He's completely insane...

Seth: Totally.

Williams: And yet, he's doing these things that are really passionate. You can sense that he really believes in what he's doing.

Seth: Oh, yeah.

Williams: Even it's...

Seth: It's crazy, but yeah, I think he's another example of someone interesting who actually got out of the mainstream in a way. It may be crazy stuff, but what other mainstream artist is out there, that passionate at that age? It's surprising actually.

Williams: A lot of them are, but they've been pushed down so far, that they can't put it into their work, that they feel nobody wants to hear about it, 'cause I've talked to a bunch of people and they all have the same kind of opinions on life and stuff, but they just don't want to put it into their work.

Seth: I can imagine that probably at this point it's hard for them to view cartooning as personal expression.

Williams: Yeah.

Seth: It's just been a job all these years.

Williams: Exactly.

Seth: I don't bother putting much personal expression into illustration. That's just, get it done and get the money.

Williams: Yeah, that's what they thought cartooning was, and yet they were so great.

Seth: I know, it's true.

I remember when I started Palooka-ville. It was right around the time I met Joe, and Chester had just started doing autobiography, and suddenly everybody seemed to be doing autobioqraphy. It occurred to me, "Gee, I don't want it to look like I'm jumping on a bandwagon." The thing was, I'd come to the conclusion that what seemed to be the most interesting work at the time was Pekar, Linda Barry and stuff like that, that seemed to be autobiographical, and it inspired me to try it myself. Then, like a year later, there was like ten people doing it, and it seemed sad. I thought, "Jesus Christ!" This autobiographical thing ... which actually, I'm getting out of soon.

Williams: Oh, really?

Seth: At the end of this storyline, the next piece I'm going to do will be fiction.

Williams: It seems like this story is not so much autobiographical as philosophical. It's your thoughts on things.

Seth: Yeah, It's certainly more constructed than a straight autobiographical piece. When I'm writing this, I'm not the least bit concerned with factual accuracy, whether I was in this spot, or that spot, or anything like that. I think that's a weakness of autobiography anyway, sticking to the facts too closely ... unless you're writing your autobiography, but I don't really think of autobiographical comics that way.

Williams: Yeah, your stuff seems to transcend it. Even Joe Matt's stuff, that's its genre, but it's not, I don't know, I would read it if he was doing It as Uncle Scrooge. I would put him on the same level as Carl Barks. I think he has a real knack for storytelling.

Seth: Yeah, Joe is what I would call a real natural talent. I don't think I've ever met anyone with so much natural talent, that's not like an intellectual talent. He just does what he does. I don't think of him the same way I do of Chester. I really think Chester is a genius, and I don't know too many people I would class as a genius. He's a really individualistic thinker. I really feel his work comes out of the intellect, where with Joe I feel like it comes out of some reserve of natural talent. They're two different approaches entirely. They're both really different.

Williams: I think he's in this lineage of storytellers in comics, there's only been a few of, like Shelly Mayer, people who just had this story in them to tell. When I get Peepshow and take it home it's the first thing I read out of the whole stack because his stories are so gripping. I'm like that with Uncle Scrooge too.

Seth: You’re right. It does have a real natural storytelling slant. It's not tricky. It's just very direct, and it really does work. I know Joe so well now it's getting hard to separate Joe and his work. I can't look at it as a casual reader anymore, because it's so connected to the creator in my mind. I'm judging it against what I know to be true or not, like how he's portraying himself and things like that...it's getting kinda close to home.

Williams: Does it get in the way of you criticizing his work?

Seth: No, I don't think so. I'm pretty brutal with Joe. We have that kind of relationship for some reason. I'm the bully and he takes it, and because of that I can be pretty harsh with him about him. We regularly, both Chester and I, both make fun of his Peepshow collection, the one from Kitchen Sink, especially those first fifteen pages. We're always picking on him for that.

(laughs) That does seem really funny to me now, when I see him in a panel saying he fancies himself a bluesman, that cracks me up. That's like a total fantasy. We always pick on him about that one. We always pick on how wrong he is about himself in those interpretations of himself in those Peepshow pages. He's pretty easy-going though. He likes constructive criticism.

Williams: Do Chester and him do it back to you?

Seth: Sure.

Williams: Do they offer you a lot of criticism?

Seth: Yes and no. It's a funny thing. With each of us, when we finish an issue, and now that Chester is back in town this is definitely true, we'll get together and let the other two read it and take criticism. But, I make it a point to only show them the issue when it's completely done. I'll take the criticism, but I'll never change anything, unless it's like a technical point. Like they say to me, "This really doesn't read, it looks like he's coming from the wrong direction," or something. I might take that and change something, same with Chester. He rarely will change anything if you don't like it, but we certainly might criticize each other back and forth.

Williams: Does it have any effect on your future work?

Seth: It might. I certainly respect their opinions, and things Chester has told me have certainly stuck in my mind and made me think about things I'm doing, especially from a technical standpoint. I have so much respect for Chester that I really will take his opinion to heart.

Williams: Are there any other artists, that you correspond with?

Seth: I have casual correspondence with other cartoonists, but really not much in the way of criticism. I correspond lightly with David Collier, but we don't really criticize each other’s work or anything. We usually just say things like, enjoyed your last issue. But yeah, it's pretty tight here in Toronto, we're very close in discussing our work with each other.

Williams: It totally helps developing as an artist to have feedback.

Seth: Yeah. Chester has been a huge inspiration to both Joe and I. He's just light years ahead. I can't underestimate how much reading Chester's work has made me re-evaluate how I think storytelling should be. I think Chester's greatest talent is how he tells a story. It's really his own approach.

Williams: I haven't read Underwater yet, but my girlfriend has read it and she was telling me about it, and I couldn't help but think of Sugar and Spike. I hate it when people try comparisons, but do you think that had any...

Seth: Influence on him? He's never read any Sugar and Spike. I was talking to him about Sugar and Spike, just in the last few weeks, 'cause I've been reading a lot of it lately, and I had to explain the premise of the strip to him because he didn't know anything about it.

Williams: Wow.

Seth: It's such a great strip.

Williams: It seems like, what he's getting at so far, from what I've heard second hand, is the idea of children's interpretation of the world.

Seth: I think you're right, but I don't know, because the truth is, Chester doesn't really tell me what he's doing, and I don't ask either, because I know he doesn't want to talk about it. He wants you to just find out as you're reading it too, but from my impression that's what he's doing. It seems to me like he's showing how a child perceives the world and how he's gradually coming to understand language and things like that. At least that's my guess. I could be completely wrong.

Williams: And that's kind of what Sugar and Spike is about too...

Seth: Sure, although certainly from a lot more entertaining point of view.

Williams: Yeah. It's kind of like a weird combination of Joe and Chester. Yeah, Shelly Mayer is a genius. Have you ever read any of his Scrlbblys?

Seth: I've only read a little bit of it 'cause I can't get my hands on the original comics.

Williams: I have one that's worth a bunch of dollars that I bought for ten bucks.

Seth: Well, I'm putting feelers out now, and I'm telling myself I'm willing to pay the money, 'cause I want to get my hands on them pretty badly. They're right at the top of my list of old comics to get my hands on.

Williams: Have you seen the Smithsonian comic book?

Seth: Oh yeah, there's a bit in there. There's also a bit in The Greatest Golden Age Comics Ever Told, from DC Comics, but just a bit, like four pages or something.

Williams: Do you like Krigstein at all?

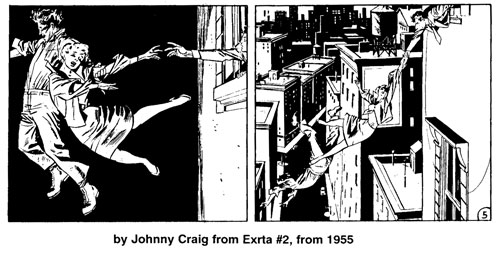

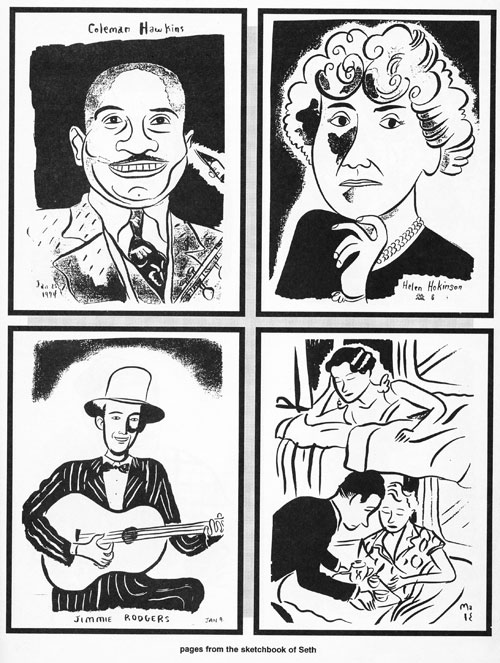

Seth: I wouldn’t say I’m not a big fan. I like him. He’s not on my big list of favorites. I like Johnny Craig better, if I had to pick between the two.

Williams: Man, that’s a strange choice. I mean, I haven’t heard other people say that. I like Craig too.

Seth: I think Craig has such a clean approach, and he tends to tell his stories less copy heavy, ‘cause he was writing most of them, whereas Krigstein was working with Feldstein or whoever. I’ve always found EC Comics way too copy heavy. So, of the EC artists, I’m definitely drawn to Kurtzman and Johnny Craig. Especially Kurtzman.

Williams: I’m doing a big thing on EC Comics for the next Destroy All Comics. I know it’s a dead horse, but…

Seth: It’s still great stuff though. It’s like a miracle that it’s all in print in hardback.

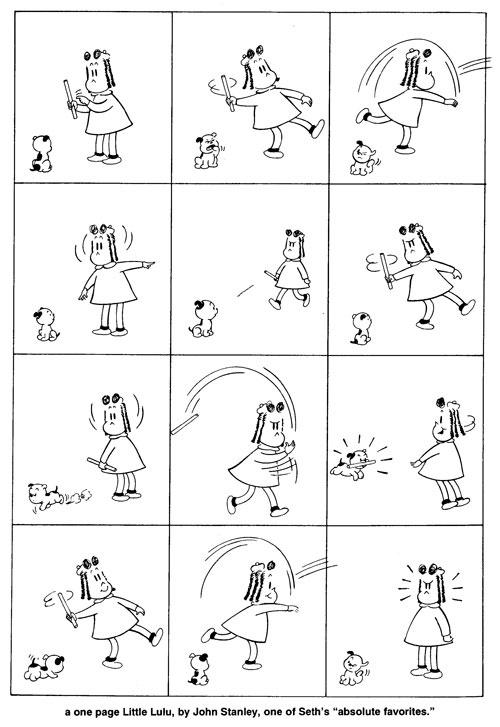

Williams: And now they’re coming out with some in a cheap format so the regular comic reader can buy it. Seth: Yeah. I wish they’d do that with the Lulu stuff. I’ve got all the hardbacks, but wouldn't it be great if kids could buy those Little Lulu comics issue by issue again. They're some of the greatest cartooning ever done, in my mind.

Williams: That's why I think it's really important to do stuff like that glossary, because I think if you bring it up enough maybe people will start to be interested in it, so that there will be a readership. For all those Popeye reprints and stuff, there was no readership, so that just failed. They all lost money and nobody ever wanted to do them again. But if as an artist, you bring up an interest, then people might…

Seth: I hope so. When I was young it worked for me. When I was reading Salinger when I was nineteen, I started to develop an interest in Japanese poetry because of it. If there was anybody whose work I liked and they talked about another artist in it, I would check it out, because I respected their opinion.

Williams: I'm making a big point in everything I do to mention something.

Seth: I'm always bringing people to the apartment and showing them stuff.

Williams: Is that a picture of your apartment on the back of the Peepshow collection?

Seth: Yeah, it is.

Williams: I was re-reading the issues of Palooka-ville, and then I went to the store and I looked at that graphic novel, 'cause you did that piece in the back and I noticed the Little Lulu's and the Tubby's all on that little rack.

Seth: Yeah, it's my place. It's Joe pretending it's his place.

Williams: He really wants to own those comics (laughs).

Seth: (laughs) I know. Well, Joe's too cheap to buy stuff. That's the problem.

Williams: Are people sending him stuff?

Seth: They send him view-master reels. I've got a few of those too. I've actually been lucky enough that a few people have sent me great cartooning stuff. I've been amazed. I got a terrific collection of this cartoonist Roland Coe, in the mail from one guy, and I was so happy. It's from 1936 or something, and it's just gorgeous stuff. And I got a couple of other old gag collections from people through the mail who just sent them to me, and I was thinking, "This story is working out well. I didn't plan on this." But keep sending it. That's always nice. And of course, you get a million mini-comics.

Williams: Which is great too. Actually, I wish I got more. I don't really get anything.

Seth: One thing that's kind of depressing about it, is sometimes you get more mini-comics then you do letters about your comic. You go to the mailbox and you see four envelopes ... and you're like, oh no, because you're kind of hoping somebody had some comments on the last issue. Even so, actually it's been going pretty good. I've been getting a fair amount of mail lately.

Williams: Your stuff is really inspiring, to me at least.

Seth: I appreciate that.

Williams: I can't criticize it, because I think it's so good. It stands on its own.

Can you describe the techniques you use, like duo-shade, and brush and painting and stuff? How do you draw your strip?

Okay. First of all I work with a light table. What I do is, I use Xerox paper... I always draw a grid out for each page, and then I do my panels one by one on separate sheets of paper, so that I can work them up at the light table, 'cause I like to do a lot of drawing on each panel until I get the compositions exactly the way I want. Then I tape that in onto the page grid. After I have the issue penciled out, I use water color paper to draw on it, so I take this penciled page and I tape it on the back of the watercolor paper, and then I just slap that on the light table, and then I just go in with a brush and ink the whole thing. After that I do an overlay for where the grays will go and that's dropped in by the printer.

Williams: Oh. Everybody was theorizing that you use duo-shade.

Seth: No. I thought about playing around with that Craft-tint paper.

Williams: That's it.

Seth: I thought about trying it around, because Roy Crane, his stuff is so great looking on it. Do you want me to talk about my color techniques?

Williams: Sure.

Seth: Basically, it's pretty straight-forward. Most of the time I work with Dr. Martins dyes for coloring. That's my basic method that I use most of the time, like the covers for numbers three and four. I just do a basic black and white drawing and then color it with Dr. Martins dyes. .

Williams: On overlay?

Seth: Nope, I dye it. Like an original watercolor painting, basically. I do a few other things, but mostly I use dyes.

Williams: The one thing I have no clue about is color.

Seth: Well, it's really something I think a lot of cartoonists have trouble with because you don't work with it that much. The first couple of years of illustration, I really had to struggle with learning color.

Williams: Did you learn it from school or...

Seth: No, l just...

Williams: Did Chester, Joe or anybody else help you?

Seth: I didn't know Joe then, and Chester just cut Rubyliths for his covers up until then. I knew in illustration I wouldn't be doing that, so I just basically decided to use Dr. Martin dyes and I spent a few months teaching myself how to use them. And for the first year of illustration I must have done every illustration over two or three times to get it right, because I just didn't have the technique figured out yet. Now it's pretty straight-forward to me. I'm still learning to do better effects with it, but it's pretty easy once you get it down. I think the real talent is finally getting to a point where you have your color choices working out, 'cause there's always a tendency to be garish at first.

Williams: The cover for the new Drawn & Quarterly is really good, and moody.

Seth: I wasn't completely satisfied with the printing. A couple of undercolors showed up on the whites, so that kind of disappointed me, but besides that, it's okay.

Williams: It has some kind of feeling.

Seth: Well. I like a lot of folk art, so that inspired me to start painting with house paint a few years ago. It's a great medium actually. It really lays down great.

Williams: Yeah.

Seth: And you can mix colors really well too, and you get a ton of paint of course, so it's really great.

Williams: I'm doing a piece in acrylics actually. It's going to be my first painted thing.

Seth: Acrylics are a good medium for easy control. I'm going to try to figure out gouache soon, actually. I know Julie Doucet does some great stuff in gouache. She's really skilled with it.

Williams: Like what kind of stuff?

Seth: Like her covers for Dirty Plotte. They were all done in gouache and a really nice job too. Fiona Smyth is really good at it too.

Williams: She's one of my favorite cartoonists nowadays.

Seth: I've known Fiona for years. She went to art school with me, actually.

Williams: She's doing the future too, for me. She's taking the past, but she's also building something new out of it.

Seth: It's interesting that she's suddenly come into comics, because she's primarily a painter. Her and Maurice Vellekoop, we all went to art school at the same time and they both entered into comics just from playing around with them for a few years, now they seem to be doing quite a lot of them.

Williams: It's a really interesting medium, as an artist.

Seth: I think so. Sure.

Williams: The possibilities are endless.

Seth: Personally, I think it's a more exciting medium than painting, because so many people get to see your work, as opposed to just a gallery show. Unless you're a huge painter, world famous. Otherwise, you're getting only a few hundred people to see your work, when in comics, even in a worst case scenario, you're getting a thousand or two.

Williams: Yeah. Does that feedback help you grow as an artist? Do you do things in stories, then people point it out?

Seth: Sometimes. I think that feedback is important. You've really got to feel like you're communicating with people. It really helps. I think that the main reason you do art is the desire to communicate something. So you definitely want some feedback.

Williams: That's a big debate with me and my friends about communications with comics. I feel like you should be making people think, and that's sometimes even more valuable than communicating.

Seth: I kind of think of them in the same level. Communicating should be something that makes people think, otherwise, there's not much point in communicating it.

Williams: Like Fiona's stuff, a lot of them, are just single images, I guess they do kind of tell a story, but it's also...

Seth: Fiona and I disagree on a basic point. She has stated that she doesn't believe plot is important. This runs completely diametrically opposed to how I view telling a story. I feel plot is extremely important. Plot meaning, basically, storytelling, to me. What draws me to comics is the storytelling potential of it, and if I wasn't interested in storytelling I'd probably be more likely to just do illustrations or drawings. So, I know we disagree on that point. Even so, I feel like you can't string a series of images together without telling some kind of a story. It's just a basic thing about cartooning. If you've got panels a story develops.

Williams: People rationalize the meaning in it.

Seth: But of course, I feel planning that at first is the most important thing.

Williams: Did you read the part in the Chris Ware interview (in Destroy All Comics #1), where he says he doesn't even really plan his stuff out ahead of time?

Seth: Yeah, I was actually kind of disappointed when I read that.

Williams: But, I think he's an exception, because I think his brain works at such a furious pace that he actually is planning it out, I just don't think he's planning it out on paper.

Seth: Yeah, you might be right...

Williams: From interviewing him I know that he's really meticulous about everything…

Seth: I feel that he must have some kind of a grand scheme of some sort when he's working on it. That's kind of how Chester works. He does things panel by panel, and whereas he doesn't plot out exactly what each panel is going to be, he does have a bigger picture of where it's going. Maybe Chris is doing that, he kind of knows where it's going, but doesn't know what's in the next panel. At least I hope so.

Williams: Do you write your stuff ahead of time?

Seth: Yeah, I do a pretty tight script.

Williams: Do you set up the shots? Do you describe the shots at all?

Seth: I do a rough breakdown for the whole issue, but it's very rough. Like I might very well change things around when I'm going, but I really like to know exactly what's going on the page, and the next page. When I'm thinking compositionally, for telling the story too, it's important for me how the pages fit with each other and how they balance each other, and of course, it's really important for me to figure out how I'm telling the story. So, it's important for me to take a shot and plan it out for the entire sequence so I can see how it flows, whether this is the right choice on how to tell it, stuff like that. I think it's very important to plot this stuff out.

Williams: It's weird to me that you actually compose each panel separately, too. That's something I wouldn't do.

Seth: It's very expedient. It's probably why I do it. The light table makes it easy, but it's really important for me that the composition be as simple as I can get it, yet still convey whatever information has to be conveyed. If I felt I could get away with it, I would throw out perspective entirely, but I don't feel like that kind of approach is really good for telling a story, unfortunately. I really like folk art, the way it's really flat. If I was to just do illustration, I would probably gravitate towards that approach, of removing perspective entirely. But, when you're telling a story, you find it's almost impossible to tell a story realistically if you don't have that level of perspective in the drawing. That kind of holds me to a more realistic approach.

Williams: Fiona, totally gets rid of everything.

Seth: Exactly, and I think that works, with when she says she doesn't think plot is important, but I think as soon as plot becomes more important, and you have to have a character walking from his apartment down to the train station, you really find that that kind of so called perspective, of reality, is a necessity. You can't convey the same feeling... maybe you could... maybe I just can't do it. I feel like it's really important for telling that kind of story.

Williams: It just depends on what kind of feelings you’re trying to convey.

Seth: Exactly.

Williams: If you want reality and human experience, then those backgrounds and those buildings really help.

Seth: I find I can't break away from it.

Williams: I do it, not only because of that, but I like old strip artists so much, and I just respect the idea of having learned how to draw perspective flawlessly, like Roy Crane does, I just think that's such a valuable thing as a person, to know.

Seth: Well, if I could draw as well as Roy Crane, I would, but I just can't reach that level. I think you have to work within your limitations. I just don't ever draw that realistically.

Williams: How often do you draw?

Seth: Every day probably.

Williams: And how long?

Seth: It all depends. It really depends on what I'm working on. With illustration and comics I'm probably drawing every single day. No, that's not true. I get some days to goof off, but if I have a lot of illustration work I might be drawing all day, or I might be drawing for just a couple of hours. When I'm working on the comic book, usually though, I'm drawing like a really long day. Like from about ten in the morning till about midnight. That's because it takes me a lot of work to get the comic done. It's really pretty concentrated work, usually. With illustration, I can slack off a bit, and maybe only draw for a few hours a day.

Williams: Wow, that's amazing. That's a lot of time,

Seth: I feel it's really good for you, though. I'm amazed how after doing illustration for five years, it really improved my drawing ability. I found the working out of a pose for a character is effortless, compared to how much work I had to put into it five years ago. It really does start to become second nature, and you can approach much more difficult drawings a lot easier. I never thought I'd get to that point. It always seemed to be a struggle.

Williams: That's the thing about doing a newspaper strip that would be so great, that you have to do it every day...

Seth: Unless you're drawing Cathy, and then you just get worse. These modern strip cartoonists don't really have much in drawing ability anyway, so...

Williams: That's the thing, me personally… I feel like you have to push yourself to do that and to get the subtlety of a Fiona Smyth emotion kind of thing, combined with the really knowing how to draw, too. I think that's the future of comics.

Seth: I think once you can really draw, you can move off into any form of stylization you want, but you still have those technical abilities to fall back on. I think this is exactly the opposite of what modern fine artists are doing. Once you have those skills you really can legitimately move in any direction, but you're held back, you're options are much limited when you don't have those skills, when you're drawing in a primitive style because that's the only style you can draw in. I think it never hurts to be able to draw well. If once you can draw well, you move into a style that doesn't display any drawing skill at all, well, that's fine. It's just a matter of having the option to choose, one way or the other.

I think so many painters I see around in the galleries and stuff, I look at it, and I can really tell that they can't draw any better. That this is the best they can do, and that's why they're doing it this way.

Williams: It's almost insulting to me, as a viewer, because it shows me that they don't really care about what they're doing. "Why do I want to look at this, you didn't put any effort into this at all?"

Seth: I agree. I think art should be a struggle. You really should have to struggle to make it good. When I'm doing illustration work, I don't struggle with it. I do the simplest approach I can. I create a composition that's effective and simple and then I can get it done in a certain amount of time.

Williams: Do you usually illustrate articles? Is that the kind of stuff you're doing?

Seth: Yeah, Yeah. Like editorial stuff. But when I'm working on the comic book I always make it a point that every single panel that I'm working on, I try to do something more complicated than I would normally do. Because, I want it to be better. I want to push myself, and that's the only way your drawing really does get better, if you keep pushing yourself. If I was just doing illustration then I'd be a hack, but comics keeps my integrity and forces me to try to do my best work.

Williams: That's really cool.

Seth: I think you can only do that if you love something too, 'cause otherwise it's just a job, and in any job you want to goof off. You don't want to have to mop the floor if you can just stand there, unless you own the place and you love it.

Williams: Exactly. That's totally how I approach comics. I do things just to make myself learn how to do things. In comics I'll do the same shot over and over again just to make myself learn how to draw it.

Seth: It's important. I think probably, the medium in the last twenty or thirty years has had its first group of artists who are really just doing it because they love it. It doesn't mean it's all good, but, it is good to have a group of artists involved in something that's just not a commercial venture.

Williams: That's the thing, comics have been this really weird beast that hasn't existed before. It's almost commercial, but then there's this creativity to it. ..

Seth: I think it's pretty exciting. Even if we never do develop a large audience, I really do feel like I'm involved with the very beginning of a really exciting art movement.

Williams: I hope so.

Seth: Yeah, if it lasts.

Williams: I think it will, because it seems like everybody just wants to do it, regardless of money.

Seth: I hope it will last. There's always the danger that it's a complete anachronism, like radio plays, or something. I mean, there are people out there who collect old radio shows, but there's no market. If you really want to do great radio plays, you might be able to do some, but there's hardly any audience. and I'm afraid that in forty years, that's what comics will be like. There will be like two-hundred people in North America who are sending their little copies to each other. It's sad that it could happen. but I'm really hoping it doesn't. I'm hoping it goes the other way, or at least stays like this.

Williams: I think it can't help but go, as long as there are people who really believe in it, and preach the virtues of it.

Seth: I hope so, I really do.

Williams: That's my mission.

Seth: I'm hoping it will grow too. I think we're in a stage now where people who would never have even done comics are considering it as an option. People who have a lot of talent, instead of ten years ago when only a few oddballs would be willing to do it, people who just loved comics. Now, you've probably got some people growing up who are about twenty years old, and might have a lot of talent, and they've seen some good comics, and they might think, "Why not go into comics," instead of thinking, "Why not go into illustration," or film making, or whatever. It's only when you start attracting greater artists, will the medium grow. I think that in a small way that's beginning.

Williams: That's really true. Another question about technique, do you letter with a brush?

Seth: Yeah, I do. I use one brush for everything. I like to use a number six.

Williams: Is that a Japanese influence at all?

Seth: No. I don't know how it started. I forced myself to learn how to use a brush six or seven years ago, and I just got really comfortable with using one brush for everything, like the same size. I don't like to switch to other tools for things, so I just make it a point to ink everything I do with the same brush. I feel it gives a real continuity to the artwork, and with the lettering matching that way.

Williams: Is it really slow?

Seth: I've never gotten my skills down on using an Ames lettering guide or anything.

Williams: Yup, I use one of those actually.

Seth: They're kind of alien to me. I've got one here, but I've never figured it out, so l just eyeball everything.

Williams: Yeah, It gives you a more natural feel. That's the one problem with the Ames thing, it gives you this kind of… I don't know, I'm using it on the Crime Clinic comic I'm doing 'cause I want that fifties comic feel, but on other stuff I don't think it's really necessary.

Seth: Strangely, I didn't even notice until my third issue, that I was using upper and lower case, and that's not normal in comics. Chester pointed it out to me, and I realized I never noticed that everybody just uses capital letters. Actually, just the capital letters is nice. It's very readable, but now I'm real comfortable with using upper and lower case.

Williams: I think with you, it speaks of the gag influence, because those artists weren't into the same kind of formulas that comic artists are into.

Seth: Definitely not. The one thing those guys really excelled at was composition, and that's something that a lot of comic book artists didn't excel at. They were better at their sheer draftsmanship.

Williams: Have you seen Jack Cole’s art?

Seth: Sure.

Williams: To me, he's the best comic artist ever.

Seth: Yeah, he's great.

Williams: His composition really works for me. He's one of the few comic artists who actually understood composition.

Seth: Sure, he's got a good compositional sense. Eisner had good compositional sense too. I think the thing about comics that's kind of forgotten, I think about ten years ago, I saw, Frank Miller said some sort of a thing about the history of comics was the history of shit. That really offended me, because there really is a phenomenal amount of high quality stuff out there, and so much of it has been forgotten. So much of it deserves reprinting. Like where is that great collection of Barnaby, by Crocket Johnson.

Williams: There was some in the seventies…

Seth: Yeah, there was those Del Rey editions too that came out, but... that's great stuff. There's tons of great stuff out there, really forgotten stuff, and it's a shame there isn't a bigger audience for these old strips too.

Williams: I had this humongous argument with Jeff, about whether there was any good things done in comics in the past, and I think half of it is that people don't see it. I mean, Krazy Kat is going out of print, and that's just a crime.

Seth: It really is. I think too, you've got to look back at the stuff with a certain historical perspective. You can't expect that some of these artists, I mean, they were working in craft, and it may not stack up against the great novelists or something, but it's still very interesting to look at. Somebody like Dan DeCarlo even, who was really a very skilled cartoonist. Those Archie stories, or the stuff he did at Marvel in the late fifties may not be great art, but it's certainly worth looking at to study a master cartoonist, showing his skills, and there were tons of these guys. Dick Sprang was a really good cartoonist.

Williams: I got to meet him and talk to him for a little bit.

Seth: Oh, did you?

Williams: He was so nice. He's just the nicest guy.

Williams: I'd like to meet him. I love his stuff. You know who no one ever mentions as a great cartoonist is Raymond Briggs. Do you know him? When The Wind Blows?

Williams: I think I saw something by him... he's written a book on how to draw comics?

Seth: I don't know. He's a British guy. He does children's books, that’s what he's known as, although his children's books are always in comic strip form. He did the Snowman, he did When The Wind Blows, he did the Man. The Bear is his newest one.

Williams: He's still doing stuff now?

Seth: Oh yeah. He's an older guy, but you should go into a children's bookstore and ask for When The Wind Blows. This is one of the greatest comic narratives ever written. It's meant for adults, and it's about nuclear war. It's such an affecting piece, you'll cry at the end of it.

Williams: I've seen a book written by him on how to draw comics, but I didn't get it 'cause I wasn't familiar with him, and I didn't have enough money or whatever.

Seth: He's really one of the all-time masters. You could put When The Wind Blows next to Maus as one of the great comics, and you never hear his name, just because he's out of the loop. He's over in the children's book world. That's part of the problem with the big picture, they don't look around.

Williams: I don't know, much to the chagrin of Chris Ware, I even see film as part of the big picture, and I see writing as part of the big picture, too.

Seth: Yes, you definitely can't just look at comics. That's too small of a world. You should hope that people doing comics are reading books and watching movies. That may sound like a strange thing for me to be saying since my current storyline is so much about comics, but I certainly don't intend to keep doing that.

Williams: What films and authors are you into?

Seth: My favorite authors, well, number one would be Salinger. I've always been a huge J.D. Salinger fan. Second on that list would be Alice Munro. She's a Canadian writer. She's in the New Yorker all the time ... she's one of the most wonderful writers ever. Her work is so sensitive and so, I don't even know how to describe it, it's just wonderful stuff. It's really well written and really insightful. Raymond Carver would be up near the top. That would probably be three of my real favorites. I usually like books that are non-genre oriented.

Williams: I can see the Salinger influence on your work. I never thought of that before, in spite of the fact that you were reading Franny and Zooey…

Seth: Salinger is somebody I've loved since I was in my late teens, and I've read the stuff a thousand times. He's another one of these people, like when I was talking about Crumb I was saying, there's certain artists that you don't feel like they influenced you, so much as when you read it they confirmed your own thoughts. Salinger is definitely one, and Woody Allen would be the third of that group. I'm a huge Woody Allen fan.

Williams: Have you read a lot of his writing?

Seth: I've read all of his writing, and it's fun, I laugh, but it's his films that are his great works.

Williams: As far as film directors he'd be your favorite?

Seth: Yeah, he'd be my favorite. I'd probably put Mike Leigh up there.

Williams: What did he do?

Seth: Did you see the film Naked? It just came out last year.

Williams: I've heard about it. People have been telling me to see it.

Seth: That was an absolutely brilliant film. That and his film ... he's done quite a few, but a lot of them you'd never see, because he did a lot of them for the BBC in England, but Life is Sweet was another great film by him. But Naked is such a work of genius. He should be winning the Academy Award this year, not that Forest Gump.

Williams: Oh god…

Seth: But nobody will pay attention to it, because it's just not a blockbuster mentality. It was an incredible film. A work of genius.

Williams: Makes me want to go see it.

Seth: You can probably get it on video. Take a look for any of Mike Leigh’s films, 'cause any of them are worth watching. He did one called Abigail's Party that's really brilliant too.

Williams: Who else?

Seth: I really like Orson Wells, of course. And I love Frank Capra, although I realize…

Williams: Do you like Preston Sturges at all?

Seth: The thing is, everybody always asks me that when I say I like Capra, but I don't really know Preston Sturges stuff very well at all. I think I've seen like one film.

Williams: To me, he's even more poignant than Capra.

Seth: Well, Capra is pretty corny, but he always sucks me in.

Williams: You're right.

Seth: He's always got me going when I'm watching Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. I'm buying into it every time,' even though I realize that his humanist philosophy isn't entirely practical, still at the end I'm feeling that stick up for the little guy attitude."

Williams: That's funny, you also say about how Schulz sucks you in too. There's this one part when you're talking about how some Peanuts are kind of trite, but it's true, those guys have a talent that comes through that, and even though I don't agree with everything they're saying, like Schulz was a pretty hardcore Christian for a while, I'm still sucked in.

Seth: I think when you're reading the work of a really talented person, a difference of opinion doesn't matter. I think the talent definitely pulls you through, and you find yourself being much more tolerant than if you were reading a more didactic work by somebody who is just preaching at you. That never sucks you in. I mean, I don't get sucked in to Ditko's philosophy. I might find it interesting that he's doing this crazy work, but not for one second is he sucking me in. He was probably sucking me in more when he was doing Spiderman or Dr. Strange. Any sort of Ayn Randian philosophy he was putting across in Spiderman would have got to me more than it would get to me through Mr. A.

Williams: Have you seen the new Dr. Strange reprint that they came out with?

Seth: Is it the hardback?

Williams: Yeah.

Seth: I thought it was really shitty looking.

Williams: Seriously? I took out the colors and compared them, and they're actually really good colors.

Seth: Oh yeah. Is this on the glossy paper? The Marvel Masterworks?

Williams: Yeah, I don't like the glossy paper either, but the colorist was actually aware of what was going on in the work. I hate all the other ones though. The Incredible Hulk one is like garbage to me to look at, because I know what it really looks like.

Seth: When I looked at the Dr. Strange one, I just thought, I'll keep my little paperback, the one I have from the seventies. I just didn't really like the production values on it.

Williams: It gets to me.

Seth: I do love that Ditko Dr. Strange stuff... Great stuff. Really beautifully drawn.

Williams: It's funny, because looking back on it, out of all the work that was done at Marvel, that's the only stuff that still stands up.

Seth: Except the Kirby. Everything Kirby stands up to me. There's no period, except maybe the very last years of his life, like Captain Victory of something, that I don't like.

Williams: OMAC doesn't stand up. Did you read OMAC?

Seth: Well, I don't like the strips. I’m not a fan of OMAC, or the New Gods, but I still think the drawing is phenomenal.

Williams: Yeah, that's true. The problem with the Kirby early Marvel stuff is it has that stupid dialog on it.

Seth: Well yeah, the stories don't read well.

Williams: I don't even read the dialog anymore. I've decided it completely doesn't exist to me.

Seth: I find his monster stuff real readable though. That stuff is so stupid, but it's fun. I can read endless amounts of that monster stuff.

Williams: In my opinion, that's where Ditko hit his peak.

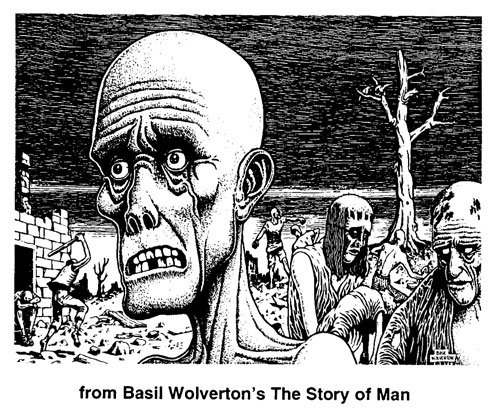

Seth: Yeah, he did great stuff there too, and some of the stories are actually not that bad. I read a few of them as a kid, that I remember actually frightened me. It's hard to believe now, when you look at them. The stories that frightened me more than anybody as a kid were Wolverton's horror stories, and the science fiction stuff that he did. They really freaked me out. There was something definitely creepy under the surface there, more so than the EC stuff that I read. I remember his stories of people turning into crabs, or those brain bats taking them over. There was something scary about this transformation that almost always went on in his stories, this loss of personal identity. They really did it to me as a kid. They kind of freaked me out.

Williams: The idea of Wolverton's stories really scared me too, actually, as a kid, his humor stuff scared me. His people, like the Mad drawings of ugly women, it's all just really bizarre. And it's so funny... the more I find out about him, he was just a jolly guy. He didn't realize how scary... Did you see the New Testament stuff he did?

Seth: Yeah, actually I owned it all for a while, then I was foolish enough to get rid of it. I tried to get it back two years ago, then it was too late. I sent away for it years ago and got it all. At some point I was stupid and I thought, "Oh, I don't want this," and I got rid of it, and I've been kicking myself ever since. It's interesting to see how he could control himself and try to keep it to a low key.

Williams: The Revelation stuff is really frightening, though.

Seth: That stuff he's pulling out all the stops. The funny thing about Wolverton is, in a lot of ways I think Wolverton was a naive artist.

Williams: Really?

Seth: I think he had a lot of skill, but I think his approach was very similar to a lot of folk artists. The fact that he didn't realize how grotesque the work was, and how affecting it was is really similar to a lot of naive artists. Also there's a real obsessive quality to his work. That hatching style is really similar to folk artists who will put every leaf on a tree, or every single rivet on a train. It's kind of an overkill approach, which is an attempt to do something realistic, and yet it achieves the exact opposite effect. I think, just reading the way Wolverton talks about things that he had a very simplistic approach to what he was doing, unlike a more intellectual artist like Kurtzman, or something.

Williams: I really want to think of Wolverton as a total genius... a conscious genius.

Seth: I don't see him that way at all.

Williams: I think you're right, I just have so much respect for it, that I… but you're right, I don't think he was aware of it.

Seth: So many of these guys, I don't think, thought of what they were doing in any higher sense.

Williams: Jack Cole just thought his comic stuff was just crap, and he didn't care about it at all.

Seth: He's a sad story.

Williams: And how. Have you seen his gag cartoons?

Seth: Yeah, I have. They're gorgeous. Man, he could control the watercolors. They were beautifully done.

Williams: He was one of those complete guys to me, who just did it all.

Seth: Yeah, he definitely was a real master when it came to cartooning.